John James Audubon Painting Reproductions 3 of 3

1785-1851

Haitian Romanticism Painter

51 Audubon Paintings

Castor fiber americanus. American Beaver 1844

Paper Art Print

$74.17

$74.17

SKU: AJJ-19666

John James Audubon

Original Size: 53.8 x 69.7 cm

Amon Carter Museum, Texas, USA

John James Audubon

Original Size: 53.8 x 69.7 cm

Amon Carter Museum, Texas, USA

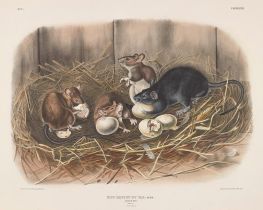

Mus rattus et var. Black Rat 1843

Paper Art Print

$75.72

$75.72

SKU: AJJ-19667

John James Audubon

Original Size: 55.6 x 71 cm

Amon Carter Museum, Texas, USA

John James Audubon

Original Size: 55.6 x 71 cm

Amon Carter Museum, Texas, USA

Didelphis virginiana, Pennant. Virginian Opossum 1845

Paper Art Print

$75.72

$75.72

SKU: AJJ-19668

John James Audubon

Original Size: 55.7 x 71 cm

Amon Carter Museum, Texas, USA

John James Audubon

Original Size: 55.7 x 71 cm

Amon Carter Museum, Texas, USA