August Macke Painting Reproductions 1 of 3

1887-1914

German Expressionist Painter

A sense of clarity runs through August Robert Ludwig Macke’s brief life, as if time itself had been compressed and sharpened for him. Born in 1887 and killed in 1914, he belonged to a generation that experienced modernity as promise and rupture almost simultaneously. German by nationality, European by temperament, Macke moved swiftly through the artistic currents of his moment, absorbing them without ever surrendering his own visual calm. His paintings offer a world in balance, even as history rushed toward catastrophe.

Meschede in Westphalia was not an obvious beginning for an artist so attuned to light and color, yet Macke’s early environment shaped his attentiveness. The family relocated first to Cologne and later to Bonn, cities whose cultural life was more varied and whose institutions provided the young painter with wider horizons. At school he formed friendships that would endure, particularly with Hans Thuar and later Walter Gerhardt. Through Gerhardt’s sister Elisabeth, whom he married in 1909, Macke gained not only emotional stability but a domestic setting that supported sustained artistic work.

Visual impressions mattered early on. Japanese woodblock prints, encountered through the Thuar household, introduced a flattened pictorial space and a decorative clarity that never entirely left him. A visit to Basel in 1900 brought him face to face with the paintings of Arnold Böcklin, whose symbolic landscapes suggested that imagination could coexist with structure. These experiences did not lead to immediate conclusions, yet they formed a visual vocabulary that Macke would later refine rather than abandon.

After his father’s death in 1904, Macke entered the Kunstakademie Düsseldorf. Academic discipline offered him technical grounding, but the institution itself proved restrictive. More formative were the activities that surrounded it - evening classes in graphic design, stage and costume work at the Schauspielhaus, and travel. Northern Italy, the Netherlands, Belgium, and Britain provided firsthand encounters with painting traditions unavailable in textbooks. Each journey expanded his sense of what painting might hold.

Paris in 1907 marked a turning point. There, Macke encountered Impressionism not as theory but as lived surface and atmosphere. Color became lighter, contours less emphatic, and scenes more attuned to modern life. A brief stay in Berlin followed, where he worked in Lovis Corinth’s studio. Corinth’s muscular handling of paint contrasted with French optical delicacy, and the tension between these approaches sharpened Macke’s own decisions.

By the end of the decade, his paintings reflected a synthesis rather than allegiance. Post-Impressionist structure met Fauvist color, yet neither overwhelmed the other. Street scenes, figures in parks, shop interiors - all appear animated but contained. Everyday modernity became his subject, not as spectacle but as rhythm. People stroll, converse, browse. Nothing dramatic occurs, and that is precisely the point.

A decisive encounter occurred in 1910 through his friendship with Franz Marc. Introduced to Wassily Kandinsky, Macke joined the circle that would become Der Blaue Reiter. While he shared the group’s resistance to academic realism, his position remained distinct. Mysticism and abstraction interested him intellectually, yet his paintings stayed anchored in the visible world. He explored symbolic color without relinquishing human presence.

Paris again altered his trajectory in 1912, this time through contact with Robert Delaunay. The chromatic energy of Delaunay’s Orphism opened new possibilities. Color could construct space rather than describe it. Macke responded immediately. Works such as the Shop Windows series fragment urban experience into overlapping planes, echoing Cubist simultaneity while preserving legibility. Movement is implied not through distortion but through juxtaposition.

Travel continued to shape his vision. Periods spent at Lake Thun introduced a quieter, reflective palette, while a journey to Tunisia in April 1914, undertaken with Paul Klee and Louis Moilliet, proved transformative. Light there behaved differently - flatter, more radiant, less burdened by shadow. In paintings from this final phase, color assumes a luminous autonomy. Türkisches Café stands among the most eloquent of these works. Figures sit in quiet proximity, architecture dissolves into color planes, and atmosphere replaces narrative.

Perhaps distance allowed clarity. Tunisia offered neither nostalgia nor urgency, only presence. In these late paintings, Macke’s long negotiation between structure and sensation finds equilibrium. Form remains intelligible, yet color leads perception. The world appears neither symbolic nor analytical, but calmly inhabited.

War shattered that calm. Mobilized shortly after the outbreak of the First World War, Macke was killed in Champagne in September 1914. He was twenty-seven. The final painting associated with him, Farewell, carries a subdued gravity, its mood shaped by knowledge rather than depiction. He was buried in Souain, far from the domestic scenes that had sustained his imagination.

August Macke’s legacy resists tragedy as explanation. His work does not announce loss; it insists on attention. In a period marked by extremes, he chose balance without retreat. Modern life, as he saw it, could be vibrant without being fractured. That vision continues to speak quietly, reminding viewers that harmony is not innocence, but a decision sustained through awareness.

Meschede in Westphalia was not an obvious beginning for an artist so attuned to light and color, yet Macke’s early environment shaped his attentiveness. The family relocated first to Cologne and later to Bonn, cities whose cultural life was more varied and whose institutions provided the young painter with wider horizons. At school he formed friendships that would endure, particularly with Hans Thuar and later Walter Gerhardt. Through Gerhardt’s sister Elisabeth, whom he married in 1909, Macke gained not only emotional stability but a domestic setting that supported sustained artistic work.

Visual impressions mattered early on. Japanese woodblock prints, encountered through the Thuar household, introduced a flattened pictorial space and a decorative clarity that never entirely left him. A visit to Basel in 1900 brought him face to face with the paintings of Arnold Böcklin, whose symbolic landscapes suggested that imagination could coexist with structure. These experiences did not lead to immediate conclusions, yet they formed a visual vocabulary that Macke would later refine rather than abandon.

After his father’s death in 1904, Macke entered the Kunstakademie Düsseldorf. Academic discipline offered him technical grounding, but the institution itself proved restrictive. More formative were the activities that surrounded it - evening classes in graphic design, stage and costume work at the Schauspielhaus, and travel. Northern Italy, the Netherlands, Belgium, and Britain provided firsthand encounters with painting traditions unavailable in textbooks. Each journey expanded his sense of what painting might hold.

Paris in 1907 marked a turning point. There, Macke encountered Impressionism not as theory but as lived surface and atmosphere. Color became lighter, contours less emphatic, and scenes more attuned to modern life. A brief stay in Berlin followed, where he worked in Lovis Corinth’s studio. Corinth’s muscular handling of paint contrasted with French optical delicacy, and the tension between these approaches sharpened Macke’s own decisions.

By the end of the decade, his paintings reflected a synthesis rather than allegiance. Post-Impressionist structure met Fauvist color, yet neither overwhelmed the other. Street scenes, figures in parks, shop interiors - all appear animated but contained. Everyday modernity became his subject, not as spectacle but as rhythm. People stroll, converse, browse. Nothing dramatic occurs, and that is precisely the point.

A decisive encounter occurred in 1910 through his friendship with Franz Marc. Introduced to Wassily Kandinsky, Macke joined the circle that would become Der Blaue Reiter. While he shared the group’s resistance to academic realism, his position remained distinct. Mysticism and abstraction interested him intellectually, yet his paintings stayed anchored in the visible world. He explored symbolic color without relinquishing human presence.

Paris again altered his trajectory in 1912, this time through contact with Robert Delaunay. The chromatic energy of Delaunay’s Orphism opened new possibilities. Color could construct space rather than describe it. Macke responded immediately. Works such as the Shop Windows series fragment urban experience into overlapping planes, echoing Cubist simultaneity while preserving legibility. Movement is implied not through distortion but through juxtaposition.

Travel continued to shape his vision. Periods spent at Lake Thun introduced a quieter, reflective palette, while a journey to Tunisia in April 1914, undertaken with Paul Klee and Louis Moilliet, proved transformative. Light there behaved differently - flatter, more radiant, less burdened by shadow. In paintings from this final phase, color assumes a luminous autonomy. Türkisches Café stands among the most eloquent of these works. Figures sit in quiet proximity, architecture dissolves into color planes, and atmosphere replaces narrative.

Perhaps distance allowed clarity. Tunisia offered neither nostalgia nor urgency, only presence. In these late paintings, Macke’s long negotiation between structure and sensation finds equilibrium. Form remains intelligible, yet color leads perception. The world appears neither symbolic nor analytical, but calmly inhabited.

War shattered that calm. Mobilized shortly after the outbreak of the First World War, Macke was killed in Champagne in September 1914. He was twenty-seven. The final painting associated with him, Farewell, carries a subdued gravity, its mood shaped by knowledge rather than depiction. He was buried in Souain, far from the domestic scenes that had sustained his imagination.

August Macke’s legacy resists tragedy as explanation. His work does not announce loss; it insists on attention. In a period marked by extremes, he chose balance without retreat. Modern life, as he saw it, could be vibrant without being fractured. That vision continues to speak quietly, reminding viewers that harmony is not innocence, but a decision sustained through awareness.

64 August Macke Paintings

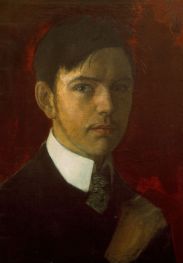

Self-Portrait 1906

Oil Painting

$479

$479

Canvas Print

$65.28

$65.28

SKU: AMK-19940

August Macke

Original Size: 54 x 35 cm

LWL-Museum für Kunst und Kultur, Munster, Germany

August Macke

Original Size: 54 x 35 cm

LWL-Museum für Kunst und Kultur, Munster, Germany

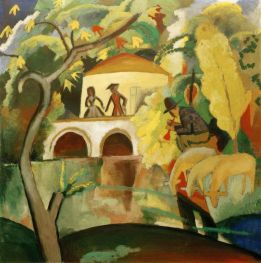

Rococo 1912

Oil Painting

$964

$964

Canvas Print

$98.93

$98.93

SKU: AMK-19941

August Macke

Original Size: 89 x 89 cm

Private Collection

August Macke

Original Size: 89 x 89 cm

Private Collection

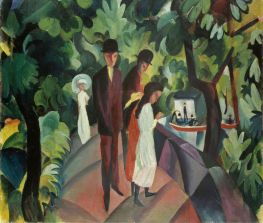

Stroll on the Bridge 1912

Oil Painting

$1116

$1116

Canvas Print

$84.00

$84.00

SKU: AMK-19942

August Macke

Original Size: 86 x 100 cm

Hessisches Landesmuseum, Darmstadt, Germany

August Macke

Original Size: 86 x 100 cm

Hessisches Landesmuseum, Darmstadt, Germany

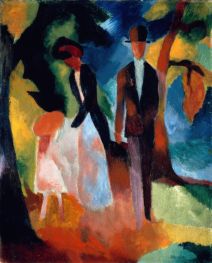

Garden Restaurant 1912

Oil Painting

$1142

$1142

Canvas Print

$75.37

$75.37

SKU: AMK-19943

August Macke

Original Size: 81 x 105 cm

Kunstmuseum, Bern, Switzerland

August Macke

Original Size: 81 x 105 cm

Kunstmuseum, Bern, Switzerland

People by a Blue Lake 1913

Oil Painting

$615

$615

Canvas Print

$79.86

$79.86

SKU: AMK-19944

August Macke

Original Size: 60 x 48.5 cm

Staatliche Kunsthalle, Karlsruhe, Germany

August Macke

Original Size: 60 x 48.5 cm

Staatliche Kunsthalle, Karlsruhe, Germany

Great Zoological Garden. Triptych 1912

Oil Painting

$2187

$2187

Canvas Print

$65.28

$65.28

SKU: AMK-19945

August Macke

Original Size: 129.5 x 230.5 cm

Museum fur Kunst und Kulturgeschichte, Dortmund, Germany

August Macke

Original Size: 129.5 x 230.5 cm

Museum fur Kunst und Kulturgeschichte, Dortmund, Germany

The Wife of the Artist 1912

Oil Painting

$996

$996

Canvas Print

$75.73

$75.73

SKU: AMK-19946

August Macke

Original Size: 105 x 81 cm

Alte Nationalgalerie, Berlin, Germany

August Macke

Original Size: 105 x 81 cm

Alte Nationalgalerie, Berlin, Germany

Girl with Fish-Bowl 1914

Oil Painting

$1091

$1091

Canvas Print

$80.04

$80.04

SKU: AMK-19947

August Macke

Original Size: 81 x 100.5 cm

Von der Heydt Museum, Wuppertal, Germany

August Macke

Original Size: 81 x 100.5 cm

Von der Heydt Museum, Wuppertal, Germany

Mrs. Elisabeth Macke with Hat 1909

Oil Painting

$604

$604

Canvas Print

$65.28

$65.28

SKU: AMK-19948

August Macke

Original Size: 49.7 x 34 cm

LWL-Museum für Kunst und Kultur, Munster, Germany

August Macke

Original Size: 49.7 x 34 cm

LWL-Museum für Kunst und Kultur, Munster, Germany

Garden with Pool 1912

Oil Painting

$588

$588

Canvas Print

$83.40

$83.40

SKU: AMK-19949

August Macke

Original Size: 51 x 50 cm

Private Collection

August Macke

Original Size: 51 x 50 cm

Private Collection

St. Mary's Church with Houses and Chimneys 1911

Oil Painting

$597

$597

Canvas Print

$86.34

$86.34

SKU: AMK-19950

August Macke

Original Size: 66 x 57.5 cm

Städtisches Kunstmuseum, Bonn, Germany

August Macke

Original Size: 66 x 57.5 cm

Städtisches Kunstmuseum, Bonn, Germany

Self-Portrait with Hat 1909

Oil Painting

$589

$589

Canvas Print

$65.28

$65.28

SKU: AMK-19951

August Macke

Original Size: 41 x 32.5 cm

Städtisches Kunstmuseum, Bonn, Germany

August Macke

Original Size: 41 x 32.5 cm

Städtisches Kunstmuseum, Bonn, Germany

Red House in a Parc 1914

Oil Painting

$807

$807

Canvas Print

$71.94

$71.94

SKU: AMK-19952

August Macke

Original Size: 60 x 82 cm

Städtisches Kunstmuseum, Bonn, Germany

August Macke

Original Size: 60 x 82 cm

Städtisches Kunstmuseum, Bonn, Germany

Children by the Fountain with Town in the Background 1914

Oil Painting

$789

$789

Canvas Print

$80.95

$80.95

SKU: AMK-19953

August Macke

Original Size: 62.5 x 75.3 cm

Städtisches Kunstmuseum, Bonn, Germany

August Macke

Original Size: 62.5 x 75.3 cm

Städtisches Kunstmuseum, Bonn, Germany

Woman on a Balcony 1910

Oil Painting

$602

$602

Canvas Print

$80.95

$80.95

SKU: AMK-19954

August Macke

Original Size: 61 x 48 cm

Städtisches Kunstmuseum, Bonn, Germany

August Macke

Original Size: 61 x 48 cm

Städtisches Kunstmuseum, Bonn, Germany

Still Life with Begonia 1914

Oil Painting

$586

$586

Canvas Print

$85.80

$85.80

SKU: AMK-19955

August Macke

Original Size: 48 x 56 cm

Städtisches Kunstmuseum, Bonn, Germany

August Macke

Original Size: 48 x 56 cm

Städtisches Kunstmuseum, Bonn, Germany

Turkish Cafe I 1914

Oil Painting

$486

$486

Canvas Print

$65.28

$65.28

SKU: AMK-19956

August Macke

Original Size: 35.5 x 25 cm

Städtisches Kunstmuseum, Bonn, Germany

August Macke

Original Size: 35.5 x 25 cm

Städtisches Kunstmuseum, Bonn, Germany

Elisabeth and Walterchen 1912

Oil Painting

$1078

$1078

Canvas Print

$79.68

$79.68

SKU: AMK-19957

August Macke

Original Size: 89 x 71 cm

Städtisches Kunstmuseum, Bonn, Germany

August Macke

Original Size: 89 x 71 cm

Städtisches Kunstmuseum, Bonn, Germany

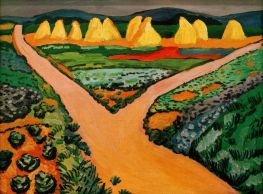

Vegetable Fields 1911

Oil Painting

$669

$669

Canvas Print

$73.21

$73.21

SKU: AMK-19958

August Macke

Original Size: 47.5 x 64 cm

Städtisches Kunstmuseum, Bonn, Germany

August Macke

Original Size: 47.5 x 64 cm

Städtisches Kunstmuseum, Bonn, Germany

Portrait of Elisabeth Gerhardt 1907

Oil Painting

$623

$623

Canvas Print

$65.28

$65.28

SKU: AMK-19959

August Macke

Original Size: 46 x 36 cm

Private Collection

August Macke

Original Size: 46 x 36 cm

Private Collection

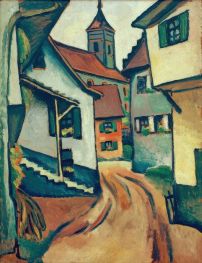

Church in Kandern 1911

Oil Painting

$583

$583

Canvas Print

$65.28

$65.28

SKU: AMK-19960

August Macke

Original Size: 30 x 35 cm

Private Collection

August Macke

Original Size: 30 x 35 cm

Private Collection

Street with Church in Kandern 1911

Oil Painting

$1110

$1110

Canvas Print

$76.09

$76.09

SKU: AMK-19961

August Macke

Original Size: 103 x 80 cm

Museum für Neue Kunst, Freiburg, Germany

August Macke

Original Size: 103 x 80 cm

Museum für Neue Kunst, Freiburg, Germany

Woman Sitting in Chair, Embroidering 1909

Oil Painting

$597

$597

Canvas Print

$80.95

$80.95

SKU: AMK-19962

August Macke

Original Size: 55 x 45 cm

Kunstmuseum, Mülheim an der Ruhr, Germany

August Macke

Original Size: 55 x 45 cm

Kunstmuseum, Mülheim an der Ruhr, Germany

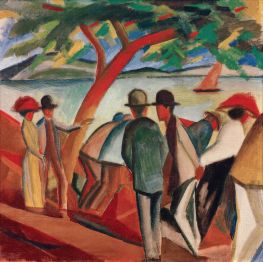

People Strolling along the Lake 1912

Oil Painting

$815

$815

Canvas Print

$98.57

$98.57

SKU: AMK-19963

August Macke

Original Size: 71.4 x 71.2 cm

Private Collection

August Macke

Original Size: 71.4 x 71.2 cm

Private Collection