Giovanni Antonio Canal Canaletto Painting Reproductions 13 of 13

1697-1768

Italian Rococo Painter

311 Canaletto Paintings

Venice: Santa Maria della Salute n.d.

Oil Painting

$5349

$5349

Canvas Print

$65.95

$65.95

SKU: CAN-17294

Giovanni Antonio Canal Canaletto

Original Size: 47.6 x 79.4 cm

Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, USA

Giovanni Antonio Canal Canaletto

Original Size: 47.6 x 79.4 cm

Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, USA

Piazza San Marco c.1727/29

Oil Painting

$9836

$9836

Canvas Print

$65.95

$65.95

SKU: CAN-17334

Giovanni Antonio Canal Canaletto

Original Size: 68.6 x 112.4 cm

Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, USA

Giovanni Antonio Canal Canaletto

Original Size: 68.6 x 112.4 cm

Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, USA

A Lock, a Column, and a Church beside a Lagoon c.1740/45

Oil Painting

$3066

$3066

Canvas Print

$73.96

$73.96

SKU: CAN-17335

Giovanni Antonio Canal Canaletto

Original Size: 50.8 x 67.6 cm

Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, USA

Giovanni Antonio Canal Canaletto

Original Size: 50.8 x 67.6 cm

Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, USA

Warwick Castle 1748

Oil Painting

$3619

$3619

Canvas Print

$65.95

$65.95

SKU: CAN-17336

Giovanni Antonio Canal Canaletto

Original Size: 43 x 71.8 cm

Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, USA

Giovanni Antonio Canal Canaletto

Original Size: 43 x 71.8 cm

Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, USA

Campo Sant'Angelo, Venice c.1730/40

Oil Painting

$4757

$4757

Canvas Print

$65.95

$65.95

SKU: CAN-17337

Giovanni Antonio Canal Canaletto

Original Size: 46.7 x 77.5 cm

Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, USA

Giovanni Antonio Canal Canaletto

Original Size: 46.7 x 77.5 cm

Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, USA

The Grand Canal, Venice, Looking South toward the ... c.1730/40

Oil Painting

$5321

$5321

Canvas Print

$65.95

$65.95

SKU: CAN-17338

Giovanni Antonio Canal Canaletto

Original Size: 46.4 x 77.5 cm

Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, USA

Giovanni Antonio Canal Canaletto

Original Size: 46.4 x 77.5 cm

Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, USA

The Grand Canal, Venice, Looking Southeast, with ... c.1730/40

Oil Painting

$5178

$5178

Canvas Print

$65.95

$65.95

SKU: CAN-17339

Giovanni Antonio Canal Canaletto

Original Size: 47 x 77.8 cm

Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, USA

Giovanni Antonio Canal Canaletto

Original Size: 47 x 77.8 cm

Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, USA

Campo Santa Maria Zobenigo, Venice c.1730/40

Oil Painting

$5002

$5002

Canvas Print

$65.95

$65.95

SKU: CAN-17340

Giovanni Antonio Canal Canaletto

Original Size: 47 x 78 cm

Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, USA

Giovanni Antonio Canal Canaletto

Original Size: 47 x 78 cm

Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, USA

Imaginary View with a Tomb by the Lagoon c.1740/45

Oil Painting

$2035

$2035

Canvas Print

$65.95

$65.95

SKU: CAN-17341

Giovanni Antonio Canal Canaletto

Original Size: 30.2 x 39.4 cm

Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, USA

Giovanni Antonio Canal Canaletto

Original Size: 30.2 x 39.4 cm

Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, USA

Imaginary View of Venice 1741

Paper Art Print

$62.44

$62.44

SKU: CAN-17342

Giovanni Antonio Canal Canaletto

Original Size: 30 x 43.7 cm

Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, USA

Giovanni Antonio Canal Canaletto

Original Size: 30 x 43.7 cm

Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, USA

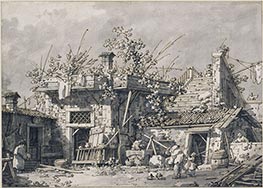

Le porte del Dolo c1735/46

Paper Art Print

$62.44

$62.44

SKU: CAN-17343

Giovanni Antonio Canal Canaletto

Original Size: 32 x 45.5 cm

Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, USA

Giovanni Antonio Canal Canaletto

Original Size: 32 x 45.5 cm

Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, USA

Capriccio with a Roman Triumphal Arch c.1720/30

Paper Art Print

$64.20

$64.20

SKU: CAN-17344

Giovanni Antonio Canal Canaletto

Original Size: 38 x 54 cm

Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, USA

Giovanni Antonio Canal Canaletto

Original Size: 38 x 54 cm

Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, USA

Warwick Castle c.1748/1749

Oil Painting

$4472

$4472

Canvas Print

$65.95

$65.95

SKU: CAN-17531

Giovanni Antonio Canal Canaletto

Original Size: 72.4 x 120 cm

Yale Center for British Art, Connecticut, USA

Giovanni Antonio Canal Canaletto

Original Size: 72.4 x 120 cm

Yale Center for British Art, Connecticut, USA

Old Walton Bridge 1755

Oil Painting

$5628

$5628

Canvas Print

$65.95

$65.95

SKU: CAN-17532

Giovanni Antonio Canal Canaletto

Original Size: 46 x 122.2 cm

Yale Center for British Art, Connecticut, USA

Giovanni Antonio Canal Canaletto

Original Size: 46 x 122.2 cm

Yale Center for British Art, Connecticut, USA

English Landscape Capriccio with a Palace c.1754

Oil Painting

$3682

$3682

Canvas Print

$80.32

$80.32

SKU: CAN-17729

Giovanni Antonio Canal Canaletto

Original Size: 134 x 108.8 cm

National Gallery of Art, Washington, USA

Giovanni Antonio Canal Canaletto

Original Size: 134 x 108.8 cm

National Gallery of Art, Washington, USA

The Porta Portello, Padua c.1741/42

Oil Painting

$3726

$3726

Canvas Print

$65.95

$65.95

SKU: CAN-17730

Giovanni Antonio Canal Canaletto

Original Size: 62 x 109 cm

National Gallery of Art, Washington, USA

Giovanni Antonio Canal Canaletto

Original Size: 62 x 109 cm

National Gallery of Art, Washington, USA

Entrance to the Grand Canal and Santa Maria della ... c.1735/40

Oil Painting

$5042

$5042

Canvas Print

$77.24

$77.24

SKU: CAN-17873

Giovanni Antonio Canal Canaletto

Original Size: 119 x 153 cm

Louvre Museum, Paris, France

Giovanni Antonio Canal Canaletto

Original Size: 119 x 153 cm

Louvre Museum, Paris, France

Capriccio with Houses on a Staircase c.1760/65

Paper Art Print

$62.44

$62.44

SKU: CAN-18798

Giovanni Antonio Canal Canaletto

Original Size: 25.1 x 35.4 cm

Gemaldegalerie, Berlin, Germany

Giovanni Antonio Canal Canaletto

Original Size: 25.1 x 35.4 cm

Gemaldegalerie, Berlin, Germany

The Portico with the Lantern c.1740/42

Paper Art Print

$62.44

$62.44

SKU: CAN-18799

Giovanni Antonio Canal Canaletto

Original Size: 29.9 x 42.6 cm

Gemaldegalerie, Berlin, Germany

Giovanni Antonio Canal Canaletto

Original Size: 29.9 x 42.6 cm

Gemaldegalerie, Berlin, Germany

The Grand Canal in Venice with the Rialto Bridge 1724

Oil Painting

$3778

$3778

Canvas Print

$65.95

$65.95

SKU: CAN-18855

Giovanni Antonio Canal Canaletto

Original Size: 65.5 x 97.5 cm

Gemaldegalerie Alte Meister, Dresden, Germany

Giovanni Antonio Canal Canaletto

Original Size: 65.5 x 97.5 cm

Gemaldegalerie Alte Meister, Dresden, Germany

Piazza San Marco, Venice c.1732/33

Oil Painting

$5221

$5221

Canvas Print

$65.95

$65.95

SKU: CAN-19006

Giovanni Antonio Canal Canaletto

Original Size: 61 x 96.5 cm

Fuji Art Museum, Tokyo, Japan

Giovanni Antonio Canal Canaletto

Original Size: 61 x 96.5 cm

Fuji Art Museum, Tokyo, Japan

View of the Palazzo del Quirinale, Rome c.1750/51

Oil Painting

$3348

$3348

Canvas Print

$65.95

$65.95

SKU: CAN-19018

Giovanni Antonio Canal Canaletto

Original Size: 39.5 x 68.5 cm

Fuji Art Museum, Tokyo, Japan

Giovanni Antonio Canal Canaletto

Original Size: 39.5 x 68.5 cm

Fuji Art Museum, Tokyo, Japan

The Bucintoro at the pier on Ascension Day c.1740

Oil Painting

$8166

$8166

Canvas Print

$73.41

$73.41

SKU: CAN-19914

Giovanni Antonio Canal Canaletto

Original Size: 120.5 x 157 cm

Pinacoteca Agnelli, Torino, Italy

Giovanni Antonio Canal Canaletto

Original Size: 120.5 x 157 cm

Pinacoteca Agnelli, Torino, Italy