Rembrandt van Rijn Painting Reproductions 5 of 13

1606-1669

Dutch Baroque Painter

296 Rembrandt Paintings

Adoration of the Magi 1632

Oil Painting

$1978

$1978

Canvas Print

$61.81

$61.81

SKU: REM-8932

van Rijn Rembrandt

Original Size: 45 x 39 cm

The State Hermitage Museum, St. Petersburg, Russia

van Rijn Rembrandt

Original Size: 45 x 39 cm

The State Hermitage Museum, St. Petersburg, Russia

Haman Recognizes His Fate 1665

Oil Painting

$2081

$2081

Canvas Print

$84.31

$84.31

SKU: REM-8933

van Rijn Rembrandt

Original Size: 127 x 116 cm

The State Hermitage Museum, St. Petersburg, Russia

van Rijn Rembrandt

Original Size: 127 x 116 cm

The State Hermitage Museum, St. Petersburg, Russia

Portrait of an Old Woman 1654

Oil Painting

$1360

$1360

Canvas Print

$73.07

$73.07

SKU: REM-8934

van Rijn Rembrandt

Original Size: 109 x 84 cm

The State Hermitage Museum, St. Petersburg, Russia

van Rijn Rembrandt

Original Size: 109 x 84 cm

The State Hermitage Museum, St. Petersburg, Russia

Portrait of a Man 1661

Oil Painting

$1604

$1604

Canvas Print

$78.87

$78.87

SKU: REM-8935

van Rijn Rembrandt

Original Size: 71 x 61 cm

The State Hermitage Museum, St. Petersburg, Russia

van Rijn Rembrandt

Original Size: 71 x 61 cm

The State Hermitage Museum, St. Petersburg, Russia

Young Woman with Earrings 1657

Oil Painting

$1410

$1410

Canvas Print

$61.81

$61.81

SKU: REM-8936

van Rijn Rembrandt

Original Size: 39.5 x 32.5 cm

The State Hermitage Museum, St. Petersburg, Russia

van Rijn Rembrandt

Original Size: 39.5 x 32.5 cm

The State Hermitage Museum, St. Petersburg, Russia

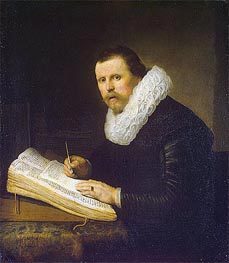

Portrait of a Scholar 1631

Oil Painting

$2229

$2229

Canvas Print

$81.77

$81.77

SKU: REM-8937

van Rijn Rembrandt

Original Size: 104.5 x 92 cm

The State Hermitage Museum, St. Petersburg, Russia

van Rijn Rembrandt

Original Size: 104.5 x 92 cm

The State Hermitage Museum, St. Petersburg, Russia

Portrait of an Old Jew 1654

Oil Painting

$1405

$1405

Canvas Print

$65.96

$65.96

SKU: REM-8938

van Rijn Rembrandt

Original Size: 109 x 85 cm

The State Hermitage Museum, St. Petersburg, Russia

van Rijn Rembrandt

Original Size: 109 x 85 cm

The State Hermitage Museum, St. Petersburg, Russia

Portrait of the Poet Jeremias de Decker 1666

Oil Painting

$1161

$1161

Canvas Print

$73.75

$73.75

SKU: REM-8939

van Rijn Rembrandt

Original Size: 71 x 56 cm

The State Hermitage Museum, St. Petersburg, Russia

van Rijn Rembrandt

Original Size: 71 x 56 cm

The State Hermitage Museum, St. Petersburg, Russia

Christ and the Woman of Samaria 1659

Oil Painting

$1207

$1207

Canvas Print

$75.29

$75.29

SKU: REM-8940

van Rijn Rembrandt

Original Size: 60 x 75 cm

The State Hermitage Museum, St. Petersburg, Russia

van Rijn Rembrandt

Original Size: 60 x 75 cm

The State Hermitage Museum, St. Petersburg, Russia

Portrait of a Young Man with a Lace Collar 1634

Oil Painting

$1775

$1775

Canvas Print

$113.53

$113.53

SKU: REM-8941

van Rijn Rembrandt

Original Size: 70.5 x 52 cm

The State Hermitage Museum, St. Petersburg, Russia

van Rijn Rembrandt

Original Size: 70.5 x 52 cm

The State Hermitage Museum, St. Petersburg, Russia

Portrait of Baertje Martens c.1640

Oil Painting

$1573

$1573

Canvas Print

$86.72

$86.72

SKU: REM-8942

van Rijn Rembrandt

Original Size: 76 x 56 cm

The State Hermitage Museum, St. Petersburg, Russia

van Rijn Rembrandt

Original Size: 76 x 56 cm

The State Hermitage Museum, St. Petersburg, Russia

Portrait of Aeltje Uylenburgh 1632

Oil Painting

$1780

$1780

Canvas Print

$69.83

$69.83

SKU: REM-8943

van Rijn Rembrandt

Original Size: 73.7 x 55.8 cm

Boston Museum of Fine Arts, Massachusetts, USA

van Rijn Rembrandt

Original Size: 73.7 x 55.8 cm

Boston Museum of Fine Arts, Massachusetts, USA

Portrait of Jan Rijcksen and his Wife, Griet Jans ... 1633

Oil Painting

$2643

$2643

Canvas Print

$61.81

$61.81

SKU: REM-8944

van Rijn Rembrandt

Original Size: 114.3 x 168.6 cm

The Royal Collection, London, UK

van Rijn Rembrandt

Original Size: 114.3 x 168.6 cm

The Royal Collection, London, UK

The Syndics (De Staalmeesters) 1662

Oil Painting

$3807

$3807

Canvas Print

$61.81

$61.81

SKU: REM-8945

van Rijn Rembrandt

Original Size: 191.5 x 279 cm

Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam, Netherlands

van Rijn Rembrandt

Original Size: 191.5 x 279 cm

Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam, Netherlands

Portrait of an Elderly Man 1667

Oil Painting

$1240

$1240

Canvas Print

$76.83

$76.83

SKU: REM-8946

van Rijn Rembrandt

Original Size: 81.9 x 67.7 cm

Mauritshuis Royal Picture Gallery, The Hague, Netherlands

van Rijn Rembrandt

Original Size: 81.9 x 67.7 cm

Mauritshuis Royal Picture Gallery, The Hague, Netherlands

Andromeda c.1631

Oil Painting

$923

$923

Canvas Print

$61.81

$61.81

SKU: REM-8947

van Rijn Rembrandt

Original Size: 34 x 24 cm

Mauritshuis Royal Picture Gallery, The Hague, Netherlands

van Rijn Rembrandt

Original Size: 34 x 24 cm

Mauritshuis Royal Picture Gallery, The Hague, Netherlands

Homer 1663

Oil Painting

$1323

$1323

Canvas Print

$70.69

$70.69

SKU: REM-8948

van Rijn Rembrandt

Original Size: 107 x 82 cm

Mauritshuis Royal Picture Gallery, The Hague, Netherlands

van Rijn Rembrandt

Original Size: 107 x 82 cm

Mauritshuis Royal Picture Gallery, The Hague, Netherlands

Smiling Man c.1629/30

Oil Painting

$835

$835

Canvas Print

$61.81

$61.81

SKU: REM-8949

van Rijn Rembrandt

Original Size: 15.4 x 12.2 cm

Mauritshuis Royal Picture Gallery, The Hague, Netherlands

van Rijn Rembrandt

Original Size: 15.4 x 12.2 cm

Mauritshuis Royal Picture Gallery, The Hague, Netherlands

Portrait of a Man with Hat with Plume c.1635/40

Oil Painting

$1357

$1357

Canvas Print

$69.67

$69.67

SKU: REM-8950

van Rijn Rembrandt

Original Size: 62.5 x 47 cm

Mauritshuis Royal Picture Gallery, The Hague, Netherlands

van Rijn Rembrandt

Original Size: 62.5 x 47 cm

Mauritshuis Royal Picture Gallery, The Hague, Netherlands

Portrait of Older Man 1650

Oil Painting

$1263

$1263

Canvas Print

$78.53

$78.53

SKU: REM-8951

van Rijn Rembrandt

Original Size: 80.5 x 66.5 cm

Mauritshuis Royal Picture Gallery, The Hague, Netherlands

van Rijn Rembrandt

Original Size: 80.5 x 66.5 cm

Mauritshuis Royal Picture Gallery, The Hague, Netherlands

Portrait of Rembrandt at around Age of 23 c.1629

Oil Painting

$994

$994

Canvas Print

$61.81

$61.81

SKU: REM-8952

van Rijn Rembrandt

Original Size: 37.9 x 28.9 cm

Mauritshuis Royal Picture Gallery, The Hague, Netherlands

van Rijn Rembrandt

Original Size: 37.9 x 28.9 cm

Mauritshuis Royal Picture Gallery, The Hague, Netherlands

Saul and David c.1650/55

Oil Painting

$1829

$1829

Canvas Print

$73.93

$73.93

SKU: REM-8953

van Rijn Rembrandt

Original Size: 130 x 164.5 cm

Mauritshuis Royal Picture Gallery, The Hague, Netherlands

van Rijn Rembrandt

Original Size: 130 x 164.5 cm

Mauritshuis Royal Picture Gallery, The Hague, Netherlands

Study of a Man's Head c.1630/31

Oil Painting

$965

$965

Canvas Print

$61.81

$61.81

SKU: REM-8954

van Rijn Rembrandt

Original Size: 46.9 x 38.8 cm

Mauritshuis Royal Picture Gallery, The Hague, Netherlands

van Rijn Rembrandt

Original Size: 46.9 x 38.8 cm

Mauritshuis Royal Picture Gallery, The Hague, Netherlands

Study of an Old Woman (Rembrandt's Mother) c.1630/35

Oil Painting

$628

$628

Canvas Print

$61.81

$61.81

SKU: REM-8955

van Rijn Rembrandt

Original Size: 18.2 x 14 cm

Mauritshuis Royal Picture Gallery, The Hague, Netherlands

van Rijn Rembrandt

Original Size: 18.2 x 14 cm

Mauritshuis Royal Picture Gallery, The Hague, Netherlands