Jan van Eyck Painting Reproductions 1 of 2

b.1395-1441

Netherlandish Northern Renaissance Painter

In a small room, a convex mirror catches the world and returns it - not as a blur of devotion or legend, but as a measured, tactile presence. A brass chandelier hangs with the calm authority of something observed, not invented. Even the silence seems painted. In that appetite for exactness, Jan van Eyck (c. before 1390 - 9 July 1441), a Flemish painter working largely in Bruges, shaped what later came to be called Early Netherlandish painting and, with it, a particular Northern way of seeing within the Early Renaissance. Rather than announcing a new age with slogans, he did it with oil, light, and the stubborn specificity of things.

Records place his origins around 1380 or 1390, often linked to Maaseik in the Maasland region - a geography that matters because dialect traces survive in notes on a preparatory drawing, and because names in this period are rarely casual. Little else about his childhood can be secured, and the silence is instructive: the first firm payments appear only when he was already “Meyster Jan den malre,” a master painter. By 1422, in The Hague, he served at the court of John of Bavaria-Straubing as painter and valet de chambre, with assistants at hand. That detail - assistants - quietly confirms his status. He arrived not as an apprentice seeking work, but as someone already operating a workshop and a professional identity.

Consider what that meant in the Binnenhof environment: rooms to redecorate, courtly schedules to navigate, reputations to protect. Court service offered security, but it also demanded tact, speed, and a controlled imagination. After John’s death in 1425, van Eyck’s path led into the Burgundian orbit. Philip the Good appointed him court painter, and the job was not merely decorative. He worked in Lille and, by 1429, settled in Bruges, where he would remain until his death. Bruges, then, becomes more than a backdrop - it is the practical engine of his mature production, the place where private devotion, mercantile wealth, and court display met one another in wood, pigment, and gilt frames.

Unusually, the Burgundian salary did not simply buy paintings; it bought a degree of autonomy. Freed from the constant churn of commissions, he could paint - as the record has it - “whenever he pleased.” That freedom is visible in the slow intelligence of his surfaces. Thin translucent glazes build colour like breath on glass, with shadows that feel earned rather than applied. The old claim that he “invented” oil painting has long been treated as an oversimplification, yet it points to a genuine historical impression: contemporaries sensed a leap in what oil could do when handled with this patience and control.

Travel, too, formed part of the job. Between 1426 and 1429 he undertook journeys for Philip described as “secret” commissions, paid at multiples of his annual salary. Not every destination can be proved, but the pattern is clear: van Eyck served as court artist and diplomat, an envoy whose eyes mattered. A better documented mission took him to Lisbon in 1428, to negotiate the duke’s marriage and to paint Isabella of Portugal so Philip could judge her appearance before the wedding. Plague made the Portuguese court itinerant, and the meeting occurred at the castle of Avis. Nine months is a long time to observe a face under political pressure. One imagines the tension - to be truthful without offense, flattering without deceit. His portraits often hold that balance: dignity without cosmetic mercy.

By 1427 his standing was public enough that he travelled to Tournai for a banquet held in his honour on the Feast of St Luke, attended by Robert Campin and Rogier van der Weyden. Such gatherings were not casual dinners; they were signals of hierarchy and belonging within the painters’ world. Soon after, van Eyck’s production tightened into a short, astonishingly dense decade. Roughly twenty surviving paintings are confidently attributed to him, most dated between 1432 and 1439, and many signed. Scarcity is part of his aura, but it also reflects how carefully finished these works are - how reluctant they seem to release a single unresolved passage.

The Ghent Altarpiece anchors the story, both because of its ambition and because it ties him to his brother Hubert, who died in 1426. The polyptych was likely begun around 1420 by Hubert and completed by Jan in 1432, then consecrated on 6 May 1432 at Saint Bavo Cathedral in Ghent. Painted for the merchant and civic figure Jodocus Vijdt and his wife Elisabeth Borluut, it speaks to a Northern confidence: a willingness to stage salvation not in ideal bodies but in observed textures - hair, stone, fabric, metal, skin. In this world, the divine does not cancel matter; it saturates it. That idea, carried by paint, changes what realism can mean.

Around 1432 he married Margaret, about fifteen years younger, and bought a house in Bruges. Their first child was born in 1434, and the marriage is glimpsed most clearly in a painted document: Portrait of Margaret van Eyck (1439), where inscription and image collaborate to declare her presence, his authorship, and her age. Van Eyck’s habit of signing - exceptional in the Netherlandish context - becomes a moral claim as much as a professional one. “ALS ICH KAN,” his motto, plays as a pun on his name, and sometimes appears in Greek characters. It can read as modesty, but it also feels like a stamp of reliability: this is done by my hand, as well as I am able.

Portraiture, in his hands, responds to a shifting social landscape. As merchant wealth grew and humanist attention to individual identity sharpened, the demand for painted likenesses spread beyond princes. Van Eyck’s early single heads - such as the small Portrait of a Man with a Blue Chaperon - establish devices that will travel far: the three-quarter view, directional light, the figure held in a narrow space against darkness, the physical closeness that insists on personhood. Even stubble becomes information. Later portraits pull the sitter slightly back, as if he learned that intensity can also be achieved through restraint.

Yet it is in the religious panels, especially the Marian images, that his control of space and symbolism becomes most complex. Mary appears as mother, as Queen of Heaven, and as a personification of the Church itself. In Madonna in the Church, her scale dominates the cathedral interior - a deliberate distortion that makes theology visible. The architecture is meticulously described and, at the same time, imaginatively recomposed, less a specific building than an ideal space of apparition. Light sources behave like arguments: a window is not just a window, but a cue for how grace enters a room. Words also matter. Inscriptions in Latin, Greek, and vernacular Dutch do not simply label; they activate the object as a tool for devotion, a painted analogue to prayer.

Look closely and he is always staging a marriage of worlds. A donor kneels in measured humility while saints appear with the quiet normality of guests entering a chamber. A tiled floor recedes with convincing perspective, yet the scene is thick with signs that require repeated viewing. Symbol and description are not opponents here; they are partners. That fusion helps explain why later artists - Petrus Christus, Hans Memling, and others - absorbed his lessons so readily. It also explains why attribution can be tense: a powerful workshop, designs completed after his death, and the long shadow of his methods complicate what “by van Eyck” can mean.

He died in Bruges on 9 July 1441 and was buried at the Church of St Donatian. Philip marked the loss with a one-off payment to the widow, equal to van Eyck’s annual salary. Lambert, another brother, appears to have overseen the workshop after Jan’s death; unfinished works were completed, designs repeated, and certain compositions lived on through copies. By 1449 an Italian humanist, Ciriaco de’ Pizzicolli, noted him as a painter of ability, and Bartolomeo Facio later named him the leading painter of his day. Fame, in other words, arrived early and travelled.

What remains compelling now is not the myth of invention, but the ethic of looking. Jan van Eyck does not flatter the world into prettiness. He holds it steady. Perhaps that steadiness required solitude - a willingness to spend time where others would move on - and perhaps the discipline of court life sharpened it further. In an age flooded with images, his paintings still ask for the oldest courtesy: slow attention, given freely, until the visible turns thoughtful.

Records place his origins around 1380 or 1390, often linked to Maaseik in the Maasland region - a geography that matters because dialect traces survive in notes on a preparatory drawing, and because names in this period are rarely casual. Little else about his childhood can be secured, and the silence is instructive: the first firm payments appear only when he was already “Meyster Jan den malre,” a master painter. By 1422, in The Hague, he served at the court of John of Bavaria-Straubing as painter and valet de chambre, with assistants at hand. That detail - assistants - quietly confirms his status. He arrived not as an apprentice seeking work, but as someone already operating a workshop and a professional identity.

Consider what that meant in the Binnenhof environment: rooms to redecorate, courtly schedules to navigate, reputations to protect. Court service offered security, but it also demanded tact, speed, and a controlled imagination. After John’s death in 1425, van Eyck’s path led into the Burgundian orbit. Philip the Good appointed him court painter, and the job was not merely decorative. He worked in Lille and, by 1429, settled in Bruges, where he would remain until his death. Bruges, then, becomes more than a backdrop - it is the practical engine of his mature production, the place where private devotion, mercantile wealth, and court display met one another in wood, pigment, and gilt frames.

Unusually, the Burgundian salary did not simply buy paintings; it bought a degree of autonomy. Freed from the constant churn of commissions, he could paint - as the record has it - “whenever he pleased.” That freedom is visible in the slow intelligence of his surfaces. Thin translucent glazes build colour like breath on glass, with shadows that feel earned rather than applied. The old claim that he “invented” oil painting has long been treated as an oversimplification, yet it points to a genuine historical impression: contemporaries sensed a leap in what oil could do when handled with this patience and control.

Travel, too, formed part of the job. Between 1426 and 1429 he undertook journeys for Philip described as “secret” commissions, paid at multiples of his annual salary. Not every destination can be proved, but the pattern is clear: van Eyck served as court artist and diplomat, an envoy whose eyes mattered. A better documented mission took him to Lisbon in 1428, to negotiate the duke’s marriage and to paint Isabella of Portugal so Philip could judge her appearance before the wedding. Plague made the Portuguese court itinerant, and the meeting occurred at the castle of Avis. Nine months is a long time to observe a face under political pressure. One imagines the tension - to be truthful without offense, flattering without deceit. His portraits often hold that balance: dignity without cosmetic mercy.

By 1427 his standing was public enough that he travelled to Tournai for a banquet held in his honour on the Feast of St Luke, attended by Robert Campin and Rogier van der Weyden. Such gatherings were not casual dinners; they were signals of hierarchy and belonging within the painters’ world. Soon after, van Eyck’s production tightened into a short, astonishingly dense decade. Roughly twenty surviving paintings are confidently attributed to him, most dated between 1432 and 1439, and many signed. Scarcity is part of his aura, but it also reflects how carefully finished these works are - how reluctant they seem to release a single unresolved passage.

The Ghent Altarpiece anchors the story, both because of its ambition and because it ties him to his brother Hubert, who died in 1426. The polyptych was likely begun around 1420 by Hubert and completed by Jan in 1432, then consecrated on 6 May 1432 at Saint Bavo Cathedral in Ghent. Painted for the merchant and civic figure Jodocus Vijdt and his wife Elisabeth Borluut, it speaks to a Northern confidence: a willingness to stage salvation not in ideal bodies but in observed textures - hair, stone, fabric, metal, skin. In this world, the divine does not cancel matter; it saturates it. That idea, carried by paint, changes what realism can mean.

Around 1432 he married Margaret, about fifteen years younger, and bought a house in Bruges. Their first child was born in 1434, and the marriage is glimpsed most clearly in a painted document: Portrait of Margaret van Eyck (1439), where inscription and image collaborate to declare her presence, his authorship, and her age. Van Eyck’s habit of signing - exceptional in the Netherlandish context - becomes a moral claim as much as a professional one. “ALS ICH KAN,” his motto, plays as a pun on his name, and sometimes appears in Greek characters. It can read as modesty, but it also feels like a stamp of reliability: this is done by my hand, as well as I am able.

Portraiture, in his hands, responds to a shifting social landscape. As merchant wealth grew and humanist attention to individual identity sharpened, the demand for painted likenesses spread beyond princes. Van Eyck’s early single heads - such as the small Portrait of a Man with a Blue Chaperon - establish devices that will travel far: the three-quarter view, directional light, the figure held in a narrow space against darkness, the physical closeness that insists on personhood. Even stubble becomes information. Later portraits pull the sitter slightly back, as if he learned that intensity can also be achieved through restraint.

Yet it is in the religious panels, especially the Marian images, that his control of space and symbolism becomes most complex. Mary appears as mother, as Queen of Heaven, and as a personification of the Church itself. In Madonna in the Church, her scale dominates the cathedral interior - a deliberate distortion that makes theology visible. The architecture is meticulously described and, at the same time, imaginatively recomposed, less a specific building than an ideal space of apparition. Light sources behave like arguments: a window is not just a window, but a cue for how grace enters a room. Words also matter. Inscriptions in Latin, Greek, and vernacular Dutch do not simply label; they activate the object as a tool for devotion, a painted analogue to prayer.

Look closely and he is always staging a marriage of worlds. A donor kneels in measured humility while saints appear with the quiet normality of guests entering a chamber. A tiled floor recedes with convincing perspective, yet the scene is thick with signs that require repeated viewing. Symbol and description are not opponents here; they are partners. That fusion helps explain why later artists - Petrus Christus, Hans Memling, and others - absorbed his lessons so readily. It also explains why attribution can be tense: a powerful workshop, designs completed after his death, and the long shadow of his methods complicate what “by van Eyck” can mean.

He died in Bruges on 9 July 1441 and was buried at the Church of St Donatian. Philip marked the loss with a one-off payment to the widow, equal to van Eyck’s annual salary. Lambert, another brother, appears to have overseen the workshop after Jan’s death; unfinished works were completed, designs repeated, and certain compositions lived on through copies. By 1449 an Italian humanist, Ciriaco de’ Pizzicolli, noted him as a painter of ability, and Bartolomeo Facio later named him the leading painter of his day. Fame, in other words, arrived early and travelled.

What remains compelling now is not the myth of invention, but the ethic of looking. Jan van Eyck does not flatter the world into prettiness. He holds it steady. Perhaps that steadiness required solitude - a willingness to spend time where others would move on - and perhaps the discipline of court life sharpened it further. In an age flooded with images, his paintings still ask for the oldest courtesy: slow attention, given freely, until the visible turns thoughtful.

42 Jan van Eyck Paintings

The Arnolfini Portrait 1434

Oil Painting

$5003

$5003

Canvas Print

$71.86

$71.86

SKU: EJV-890

Jan van Eyck

Original Size: 82.2 x 60 cm

National Gallery, London, UK

Jan van Eyck

Original Size: 82.2 x 60 cm

National Gallery, London, UK

A Man in a Turban (Possibly a Self-Portrait) 1433

Oil Painting

$1801

$1801

Canvas Print

$65.03

$65.03

SKU: EJV-891

Jan van Eyck

Original Size: 26 x 19 cm

National Gallery, London, UK

Jan van Eyck

Original Size: 26 x 19 cm

National Gallery, London, UK

Virgin and Child, with Saints and Donor c.1441

Oil Painting

$9519

$9519

Canvas Print

$94.31

$94.31

SKU: EJV-892

Jan van Eyck

Original Size: 47.3 x 61.2 cm

Frick Collection, New York, USA

Jan van Eyck

Original Size: 47.3 x 61.2 cm

Frick Collection, New York, USA

The Virgin of Chancellor Rolin c.1435

Oil Painting

$16417

$16417

Canvas Print

$93.18

$93.18

SKU: EJV-3172

Jan van Eyck

Original Size: 66 x 62 cm

Louvre Museum, Paris, France

Jan van Eyck

Original Size: 66 x 62 cm

Louvre Museum, Paris, France

Portrait of Giovanni Arnolfini c.1438

Oil Painting

$1026

$1026

Canvas Print

$65.03

$65.03

SKU: EJV-3173

Jan van Eyck

Original Size: 30 x 21.6 cm

Alte Nationalgalerie, Berlin, Germany

Jan van Eyck

Original Size: 30 x 21.6 cm

Alte Nationalgalerie, Berlin, Germany

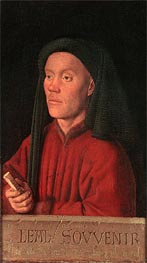

Portrait of a Man (Leal Souvenir) 1432

Oil Painting

$1374

$1374

Canvas Print

$65.03

$65.03

SKU: EJV-3174

Jan van Eyck

Original Size: 33.3 x 18.9 cm

National Gallery, London, UK

Jan van Eyck

Original Size: 33.3 x 18.9 cm

National Gallery, London, UK

Cardinal Niccolo Albergati c.1435

Oil Painting

$1746

$1746

Canvas Print

$65.03

$65.03

SKU: EJV-3178

Jan van Eyck

Original Size: 34 x 27.3 cm

Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna, Austria

Jan van Eyck

Original Size: 34 x 27.3 cm

Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna, Austria

Madonna at the Fountain 1439

Oil Painting

$1943

$1943

Canvas Print

$65.03

$65.03

SKU: EJV-7840

Jan van Eyck

Original Size: 19 x 12 cm

Koninklijk Royal Museum of Fine Arts, Antwerp, Belgium

Jan van Eyck

Original Size: 19 x 12 cm

Koninklijk Royal Museum of Fine Arts, Antwerp, Belgium

Christ n.d.

Oil Painting

$1903

$1903

Canvas Print

$65.03

$65.03

SKU: EJV-7841

Jan van Eyck

Original Size: 33.3 x 26.6 cm

Groeninge Museum, Bruges, Belgium

Jan van Eyck

Original Size: 33.3 x 26.6 cm

Groeninge Museum, Bruges, Belgium

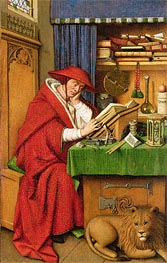

Saint Jerome in His Study c.1435

Oil Painting

$2103

$2103

Canvas Print

$65.03

$65.03

SKU: EJV-7842

Jan van Eyck

Original Size: 19.9 x 12.5 cm

Detroit Institute of Arts, Michigan, USA

Jan van Eyck

Original Size: 19.9 x 12.5 cm

Detroit Institute of Arts, Michigan, USA

St. Barbara 1437

Canvas Print

$65.03

$65.03

SKU: EJV-7843

Jan van Eyck

Original Size: 31 x 18 cm

Koninklijk Royal Museum of Fine Arts, Antwerp, Belgium

Jan van Eyck

Original Size: 31 x 18 cm

Koninklijk Royal Museum of Fine Arts, Antwerp, Belgium

The Lucca-Madonna n.d.

Oil Painting

$3546

$3546

Canvas Print

$72.75

$72.75

SKU: EJV-7844

Jan van Eyck

Original Size: 65.5 x 49.5 cm

Städel Museum, Frankfurt, Germany

Jan van Eyck

Original Size: 65.5 x 49.5 cm

Städel Museum, Frankfurt, Germany

The Virgin and Child with Canon Joris Van der Paele 1436

Oil Painting

$18980

$18980

Canvas Print

$75.62

$75.62

SKU: EJV-7845

Jan van Eyck

Original Size: 122.1 x 157.8 cm

Groeninge Museum, Bruges, Belgium

Jan van Eyck

Original Size: 122.1 x 157.8 cm

Groeninge Museum, Bruges, Belgium

Portrait of Margareta van Eyck 1439

Oil Painting

$1903

$1903

Canvas Print

$65.03

$65.03

SKU: EJV-7846

Jan van Eyck

Original Size: 32.6 x 25.8 cm

Groeninge Museum, Bruges, Belgium

Jan van Eyck

Original Size: 32.6 x 25.8 cm

Groeninge Museum, Bruges, Belgium

Christ, God the Father (Ghent Altarpiece) n.d.

Oil Painting

$3980

$3980

Canvas Print

$65.03

$65.03

SKU: EJV-7847

Jan van Eyck

Original Size: unknown

Saint Bavo Cathedral, Ghent, Belgium

Jan van Eyck

Original Size: unknown

Saint Bavo Cathedral, Ghent, Belgium

The Annunciation c.1434/36

Oil Painting

$3593

$3593

Canvas Print

$65.03

$65.03

SKU: EJV-7852

Jan van Eyck

Original Size: 90.2 x 34.1 cm

National Gallery of Art, Washington, USA

Jan van Eyck

Original Size: 90.2 x 34.1 cm

National Gallery of Art, Washington, USA

Saint Christopher c.1440/50

Oil Painting

$2000

$2000

Canvas Print

$65.03

$65.03

SKU: EJV-7853

Jan van Eyck

Original Size: 29.5 x 21.1 cm

Philadelphia Museum of Art, Pennsylvania, USA

Jan van Eyck

Original Size: 29.5 x 21.1 cm

Philadelphia Museum of Art, Pennsylvania, USA

Saint Francis of Assisi Receiving the Stigmata c.1438/40

Oil Painting

$3266

$3266

Canvas Print

$65.03

$65.03

SKU: EJV-7854

Jan van Eyck

Original Size: 12.7 x 14.6 cm

Philadelphia Museum of Art, Pennsylvania, USA

Jan van Eyck

Original Size: 12.7 x 14.6 cm

Philadelphia Museum of Art, Pennsylvania, USA

The Fountain of Grace and the Triumph of the ... 1430

Oil Painting

$33252

$33252

Canvas Print

$65.03

$65.03

SKU: EJV-7855

Jan van Eyck

Original Size: 181 x 119 cm

Prado Museum, Madrid, Spain

Jan van Eyck

Original Size: 181 x 119 cm

Prado Museum, Madrid, Spain

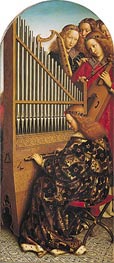

The Singing Angels (The Ghent Altarpiece) 1432

Oil Painting

$9889

$9889

Canvas Print

$65.03

$65.03

SKU: EJV-7856

Jan van Eyck

Original Size: unknown

Saint Bavo Cathedral, Ghent, Belgium

Jan van Eyck

Original Size: unknown

Saint Bavo Cathedral, Ghent, Belgium

The Virgin Mary (The Ghent Altarpiece) 1432

Oil Painting

$3908

$3908

Canvas Print

$65.03

$65.03

SKU: EJV-7857

Jan van Eyck

Original Size: unknown

Saint Bavo Cathedral, Ghent, Belgium

Jan van Eyck

Original Size: unknown

Saint Bavo Cathedral, Ghent, Belgium

John the Baptist (The Ghent Altarpiece) 1432

Oil Painting

$3546

$3546

Canvas Print

$71.71

$71.71

SKU: EJV-7858

Jan van Eyck

Original Size: unknown

Saint Bavo Cathedral, Ghent, Belgium

Jan van Eyck

Original Size: unknown

Saint Bavo Cathedral, Ghent, Belgium

Angels Playing Music (The Ghent Altarpiece) 1432

Oil Painting

$3660

$3660

Canvas Print

$71.71

$71.71

SKU: EJV-7859

Jan van Eyck

Original Size: unknown

Saint Bavo Cathedral, Ghent, Belgium

Jan van Eyck

Original Size: unknown

Saint Bavo Cathedral, Ghent, Belgium

The Just Judges (The Ghent Altarpiece) 1432

Oil Painting

$6163

$6163

Canvas Print

$65.03

$65.03

SKU: EJV-7860

Jan van Eyck

Original Size: unknown

Saint Bavo Cathedral, Ghent, Belgium

Jan van Eyck

Original Size: unknown

Saint Bavo Cathedral, Ghent, Belgium