Giacomo Balla Painting Reproductions 1 of 1

1871-1958

Italian Futurist Painter

Turin at the fin de siècle offered a paradoxical setting for a modernist: provincial yet industrial, steeped in Savoyard prudence yet already echoing with the hiss of locomotives. Into this turbulence Giacomo Balla was born on 18 July 1871, the son of a chemist whose amateur photographs must have impressed the boy with the lure of arrested light. The father’s early death, and the consequent drudgery of a lithography shop, tempered Balla’s vision with the discipline of craft - an apprenticeship to the material facts of ink, paper, and the mechanics of reproduction.

By his twenties Balla had exchanged the margins of Piedmont for Rome’s ferment. At the Udienza he absorbed the scientific chromatics of Divisionism, metabolising Seurat’s froideur into something more mercurial. Teaching the young Boccioni and Severini around 1902, he served as conduit between post-Impressionist experiment and the still-to-be-named Futurism. Yet while those pupils gravitated to metal and manifest destiny, Balla retained a lyricism rooted less in machinery than in optics - a conviction that energy could be visualised through velocity of brush and flicker of pigment.

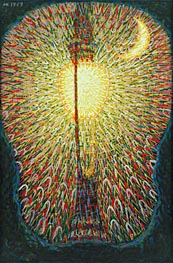

His submission to the Venice Biennale of 1909, The Street Light, made explicit this credo. The lamp’s fan-shaped corona, radiating in prismatic shards, reframed an everyday object as a prism of perception. It announced a painter preoccupied not with what the eye sees but with how vision itself behaves. Small wonder that, within a year, Balla’s signature joined Marinetti’s Futurist manifesto. Yet he arrived as the elder statesman: close to forty, established, and wary of the bombast that enthralled his juniors. Where they trumpeted trains, he scrutinised the shuffle of feet; where they exalted violence, he charted the tremor of a violinist’s wrist.

Dynamism of a Dog on a Leash (1912) distilled this focus. The petite dachshund, multiplied into a radial blur of paws, tail, and tether, renders movement by denying singularity. What emerges is neither narrative nor portrait but a diagram of time sliced into increments, reminiscent of chronophotography yet resolved through paint’s supple translucence. The same period yielded Iridescent Interpenetration, a sequence of near-abstract panels in which saturated triangles interlock like refracted sunbeams. Here Balla displaced object altogether, pursuing light as both subject and medium - a sensibility closer to Kandinsky’s synaesthetic speculations than to Futurism’s clangorous rhetoric.

Restless invention propelled him beyond canvas. The 1914 Technical Manifesto on Futurist Painting exhorted artists to capture “the dynamic sensation itself”, a phrase that found corollary in his sculptural Boccioni’s Fist (1915) and in his designs for antineutral clothing - zig-zagging seams intended to set the body ablaze with implied speed. Furniture, stage sets, even typography passed through his atelier, each project an argument that aesthetics and daily life ought to interpenetrate, altering consciousness at every scale.

History, however, intervened. Early enthusiasm for the nascent Fascist regime cooled as Balla perceived its instrumentalisation of art. By the early 1930s he renounced abstraction, adopting an almost pastoral naturalism that puzzled critics and confirmed his outsider status. For two decades he painted largely in isolation, his futurist canvases gathering dust while younger movements rehearsed, with fresh accents, the problems he had posed a generation earlier.

Recognition returned slowly after 1945, quickening with documenta 8 in 1987, where his experiments appeared prophetic beside post-war kineticism. Today Balla is understood less as Futurism’s stylistic curiosity and more as a bridge between nineteenth-century optical science and the immaterial preoccupations of modernity. His oeuvre, spanning flickering street lamps to crystalline abstractions, testifies to a mind convinced that painting could translate the pulse of life onto a static surface - and thereby remind viewers that perception is itself a constant act of renewal.

By his twenties Balla had exchanged the margins of Piedmont for Rome’s ferment. At the Udienza he absorbed the scientific chromatics of Divisionism, metabolising Seurat’s froideur into something more mercurial. Teaching the young Boccioni and Severini around 1902, he served as conduit between post-Impressionist experiment and the still-to-be-named Futurism. Yet while those pupils gravitated to metal and manifest destiny, Balla retained a lyricism rooted less in machinery than in optics - a conviction that energy could be visualised through velocity of brush and flicker of pigment.

His submission to the Venice Biennale of 1909, The Street Light, made explicit this credo. The lamp’s fan-shaped corona, radiating in prismatic shards, reframed an everyday object as a prism of perception. It announced a painter preoccupied not with what the eye sees but with how vision itself behaves. Small wonder that, within a year, Balla’s signature joined Marinetti’s Futurist manifesto. Yet he arrived as the elder statesman: close to forty, established, and wary of the bombast that enthralled his juniors. Where they trumpeted trains, he scrutinised the shuffle of feet; where they exalted violence, he charted the tremor of a violinist’s wrist.

Dynamism of a Dog on a Leash (1912) distilled this focus. The petite dachshund, multiplied into a radial blur of paws, tail, and tether, renders movement by denying singularity. What emerges is neither narrative nor portrait but a diagram of time sliced into increments, reminiscent of chronophotography yet resolved through paint’s supple translucence. The same period yielded Iridescent Interpenetration, a sequence of near-abstract panels in which saturated triangles interlock like refracted sunbeams. Here Balla displaced object altogether, pursuing light as both subject and medium - a sensibility closer to Kandinsky’s synaesthetic speculations than to Futurism’s clangorous rhetoric.

Restless invention propelled him beyond canvas. The 1914 Technical Manifesto on Futurist Painting exhorted artists to capture “the dynamic sensation itself”, a phrase that found corollary in his sculptural Boccioni’s Fist (1915) and in his designs for antineutral clothing - zig-zagging seams intended to set the body ablaze with implied speed. Furniture, stage sets, even typography passed through his atelier, each project an argument that aesthetics and daily life ought to interpenetrate, altering consciousness at every scale.

History, however, intervened. Early enthusiasm for the nascent Fascist regime cooled as Balla perceived its instrumentalisation of art. By the early 1930s he renounced abstraction, adopting an almost pastoral naturalism that puzzled critics and confirmed his outsider status. For two decades he painted largely in isolation, his futurist canvases gathering dust while younger movements rehearsed, with fresh accents, the problems he had posed a generation earlier.

Recognition returned slowly after 1945, quickening with documenta 8 in 1987, where his experiments appeared prophetic beside post-war kineticism. Today Balla is understood less as Futurism’s stylistic curiosity and more as a bridge between nineteenth-century optical science and the immaterial preoccupations of modernity. His oeuvre, spanning flickering street lamps to crystalline abstractions, testifies to a mind convinced that painting could translate the pulse of life onto a static surface - and thereby remind viewers that perception is itself a constant act of renewal.

3 Giacomo Balla Paintings

Street Light 1909

Oil Painting

$1727

$1727

Canvas Print

$65.95

$65.95

SKU: BGI-13365

Giacomo Balla

Original Size: 174.7 x 114.7 cm

Museum of Modern Art, New York, USA

Giacomo Balla

Original Size: 174.7 x 114.7 cm

Museum of Modern Art, New York, USA

Dynamism of a Dog on a Leash 1912

Oil Painting

$1139

$1139

Canvas Print

$82.13

$82.13

SKU: BGI-19912

Giacomo Balla

Original Size: 89.8 x 110 cm

Albright-Knox Art Gallery, Buffalo, USA

Giacomo Balla

Original Size: 89.8 x 110 cm

Albright-Knox Art Gallery, Buffalo, USA

Abstract Speed 1913

Oil Painting

$3113

$3113

Canvas Print

$78.14

$78.14

SKU: BGI-19913

Giacomo Balla

Original Size: 260 x 332 cm

Pinacoteca Agnelli, Torino, Italy

Giacomo Balla

Original Size: 260 x 332 cm

Pinacoteca Agnelli, Torino, Italy