Joseph Ducreux Painting Reproductions 1 of 1

1735-1802

French Rococo Painter

Born in Nancy in 1735, Joseph Ducreux occupies a peculiarly revealing niche within late-Enlightenment portraiture. Both court insider and restless experimenter, he negotiated the passage from ancien régime ceremonial to revolutionary volatility with a composure that still appears modern. His pastels and canvases pursue expressive verisimilitude - the speaking face rather than the frozen mask - while his itinerant career illustrates the precarious fortunes of an artist dependent on unstable patronage.

Ducreux’s first instruction almost certainly came from his father - a provincial painter who supplied him with technical basics and professional expectations. The decisive turn arrived in 1760, when the young artist entered the Parisian atelier of Maurice-Quentin de La Tour, the virtuoso pastellist celebrated for animated likenesses. There he absorbed an insistence on the vivacity of the sitter’s glance and the unforced fall of drapery. Exposure to Jean-Baptiste Greuze soon followed, furnishing a looser, more painterly oil technique that would temper pastel precision with an appealing softness.

Recognition came quickly. In 1769 the French court dispatched Ducreux to Vienna to produce a miniature of the adolescent archduchess Marie Antoinette prior to her marriage to the dauphin. The success of that diminutive likeness won him a barony and the unprecedented title of premier peintre de la reine - an honor that placed a non-Academician above many entrenched rivals. Within Versailles he cultivated an atmosphere of easy rapport, coaxing from his royal sitters a degree of informality that subtly undermined rigid hierarchies even as it decorated them.

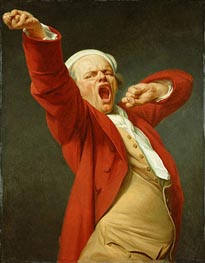

What distinguishes Ducreux from more conventional contemporaries is his systematic engagement with physiognomy, the pseudoscientific conviction that inner character is legible on the face. Rather than polite serenity, his portraits reveal caught moments: the furtive plea for silence in Le Discret, the cavernous yawn that opens the celebrated self-portrait of 1783, the conspiratorial laugh and pointing finger of the moqueur around 1793. The artist treats his own visage as laboratory material, extending the range of acceptable expression and, by extension, the psychological gamut of eighteenth-century portraiture.

The French Revolution fractured the genteel environment that had fostered his ascent. Anticipating danger, Ducreux withdrew to London, where in 1792 he captured the exiled Louis XVI in a final chalk portrait remarkable for its subdued dignity. The image, created on the eve of regicide, underscores the artist’s capacity to balance sympathy and observation without surrendering to sentiment. It also demonstrates the resilience of his practice, adaptable to new locales and hostile climates.

Returning to Paris in 1793, he found in Jacques-Louis David an unexpected ally. David, dominating the artistic machinery of the Convention, secured Ducreux official commissions and helped transform his residence into a convivial salon frequented by painters, writers, and musicians such as Étienne Méhul. There the baron’s disciplined curiosity proved contagious, and younger artists absorbed his insistence on spontaneity, even while public taste pivoted toward the heroic austerity of neoclassicism.

Personal life threaded through these professional upheavals. Of his many children, Jules died a soldier-painter at Jemappes, while Rose-Adélaïde and Antoinette-Clémence inherited the brush, their refined self-portraits testifying to paternal example. The family narrative, punctured by loss yet sustained by shared vocation, hints at Ducreux’s pedagogic generosity, an extension of the empathic acuity visible in his portraits.

He died suddenly of apoplexy on 24 July 1802 during a walk toward Saint-Denis. Posterity, slow to disentangle his unsigned works from misattributions, has only recently begun to recognise his originality. Today Ducreux stands as a transitional figure - technically versatile, psychologically adventurous, and alert to the possibilities of art beyond decorum. His canvases, at once intimate and interrogative, invite us to witness the eighteenth century thinking aloud.

Ducreux’s first instruction almost certainly came from his father - a provincial painter who supplied him with technical basics and professional expectations. The decisive turn arrived in 1760, when the young artist entered the Parisian atelier of Maurice-Quentin de La Tour, the virtuoso pastellist celebrated for animated likenesses. There he absorbed an insistence on the vivacity of the sitter’s glance and the unforced fall of drapery. Exposure to Jean-Baptiste Greuze soon followed, furnishing a looser, more painterly oil technique that would temper pastel precision with an appealing softness.

Recognition came quickly. In 1769 the French court dispatched Ducreux to Vienna to produce a miniature of the adolescent archduchess Marie Antoinette prior to her marriage to the dauphin. The success of that diminutive likeness won him a barony and the unprecedented title of premier peintre de la reine - an honor that placed a non-Academician above many entrenched rivals. Within Versailles he cultivated an atmosphere of easy rapport, coaxing from his royal sitters a degree of informality that subtly undermined rigid hierarchies even as it decorated them.

What distinguishes Ducreux from more conventional contemporaries is his systematic engagement with physiognomy, the pseudoscientific conviction that inner character is legible on the face. Rather than polite serenity, his portraits reveal caught moments: the furtive plea for silence in Le Discret, the cavernous yawn that opens the celebrated self-portrait of 1783, the conspiratorial laugh and pointing finger of the moqueur around 1793. The artist treats his own visage as laboratory material, extending the range of acceptable expression and, by extension, the psychological gamut of eighteenth-century portraiture.

The French Revolution fractured the genteel environment that had fostered his ascent. Anticipating danger, Ducreux withdrew to London, where in 1792 he captured the exiled Louis XVI in a final chalk portrait remarkable for its subdued dignity. The image, created on the eve of regicide, underscores the artist’s capacity to balance sympathy and observation without surrendering to sentiment. It also demonstrates the resilience of his practice, adaptable to new locales and hostile climates.

Returning to Paris in 1793, he found in Jacques-Louis David an unexpected ally. David, dominating the artistic machinery of the Convention, secured Ducreux official commissions and helped transform his residence into a convivial salon frequented by painters, writers, and musicians such as Étienne Méhul. There the baron’s disciplined curiosity proved contagious, and younger artists absorbed his insistence on spontaneity, even while public taste pivoted toward the heroic austerity of neoclassicism.

Personal life threaded through these professional upheavals. Of his many children, Jules died a soldier-painter at Jemappes, while Rose-Adélaïde and Antoinette-Clémence inherited the brush, their refined self-portraits testifying to paternal example. The family narrative, punctured by loss yet sustained by shared vocation, hints at Ducreux’s pedagogic generosity, an extension of the empathic acuity visible in his portraits.

He died suddenly of apoplexy on 24 July 1802 during a walk toward Saint-Denis. Posterity, slow to disentangle his unsigned works from misattributions, has only recently begun to recognise his originality. Today Ducreux stands as a transitional figure - technically versatile, psychologically adventurous, and alert to the possibilities of art beyond decorum. His canvases, at once intimate and interrogative, invite us to witness the eighteenth century thinking aloud.

3 Joseph Ducreux Paintings

Portrait of Marie Antoinette de Habsbourg-Lorraine n.d.

Oil Painting

$1588

$1588

Canvas Print

$76.42

$76.42

SKU: DUJ-4323

Joseph Ducreux

Original Size: 64.5 x 53.3 cm

Boston Museum of Fine Arts, Massachusetts, USA

Joseph Ducreux

Original Size: 64.5 x 53.3 cm

Boston Museum of Fine Arts, Massachusetts, USA

Self Portrait Yawning c.1780

Oil Painting

$2173

$2173

Canvas Print

$71.32

$71.32

SKU: DUJ-4324

Joseph Ducreux

Original Size: 117.8 x 90.8 cm

J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles, USA

Joseph Ducreux

Original Size: 117.8 x 90.8 cm

J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles, USA

Self Portrait c.1793

Oil Painting

$1870

$1870

SKU: DUJ-4325

Joseph Ducreux

Original Size: unknown

Private Collection

Joseph Ducreux

Original Size: unknown

Private Collection