Jean-Francois Millet Painting Reproductions 1 of 1

1814-1875

French Realist Painter

Jean-François Millet was born on 4 October 1814 in the hamlet of Gruchy, near Gréville in Normandy, the eldest son of sturdy, God-fearing farmers whose days were regulated by weather, labour, and liturgy. His earliest education came from village priests who taught him Latin and a taste for Virgil, yet the imperatives of the land soon reclaimed him. He learned to mow, bind sheaves, winnow, spread manure - actions that later reappeared as motifs, transmuted into pictorial structure. The memory of those repetitive gestures supplied not sentiment but a grammar of form.

In 1833 his father sent him to Cherbourg, first to Bon Du Mouchel, then to Théophile Langlois de Chèvreville, a follower of Baron Gros. These provincial ateliers offered craft rather than doctrine, enough to propel a stipend that in 1837 delivered him to Paris and the École des Beaux-Arts, where he studied briefly under Paul Delaroche. The metropolis did not embrace him. His scholarship lapsed in 1839, and the Salon rejected his Saint Anne Instructing the Virgin. Paris, volatile and crowded, demanded novelty and finish; Millet, still searching, retreated to Cherbourg.

Accepted at the Salon in 1840 with a portrait, he flirted with the genre that promised quickest payment - likenesses for the bourgeoisie - yet found the enterprise arid. Marriage to Pauline-Virginie Ono in 1841 brought him back to Paris, but rejection at the 1843 Salon and Pauline’s death from consumption in 1844 fractured his footing. By 1845 he was in Le Havre with Catherine Lemaire, who would bear him nine children and become his wife in a civil ceremony in 1853. Domestic obligation sharpened his pragmatism: portraits, small canvases, whatever sold.

The mid-1840s also brought friendships that mattered: Troyon, Diaz, Jacque, Rousseau - painters who, like him, turned their backs on Parisian façades for the Forest of Fontainebleau; Daumier, whose draughtsmanship and moral gravity offered a model; and Alfred Sensier, later his biographer and intermittent financial lifeline. In 1847 Millet tasted official success with Oedipus Taken down from the Tree; the next year, the state bought The Winnower. Ambition swelled. He unveiled The Captivity of the Jews in Babylon at the Salon of 1848 - large, grand, rejected by critics. He eventually painted over it. X-rays of The Young Shepherdess (1870) reveal Captivity beneath - a palimpsest born of wartime scarcity and changing convictions.

In June 1849 he settled in Barbizon, a village at the forest’s edge. The move was not mere retreat but strategic reorientation. There he could make peasant life the sustained subject, not anecdote. Shepherdess Sitting at the Edge of the Forest signalled a turn from pastoral convention toward unvarnished observation. Sensier’s 1850 arrangement - money and materials in exchange for works, without exclusivity - gave him breathing room. That year he exhibited The Sower. The figure, striding against twilight, became an emblem: not heroic rhetoric but monumental necessity.

From 1850 to 1853 he laboured over Harvesters Resting (Ruth and Boaz), his only dated painting and the one he considered his most significant. It attempted to reconcile biblical gravitas with contemporary toil, Michelangelo’s sculptural weight with Poussin’s measured order. The Salon awarded it a second-class medal. Meanwhile he etched - Man with a Wheelbarrow, Woman Carding Wool - concise essays in line and burden. His focus narrowed to the daily dramas of labour: sowing, gleaning, milking, shearing.

The Gleaners of 1857, prepared through years of sketches and an earlier vertical version, brought him notoriety. The public saw poverty and social unrest; Millet proposed endurance and rhythm. Three women bend and rise, their backs tracing arcs that echo the cyclical labour of the poor. The distant stacks of grain and a setting sun imply abundance withheld. His palette’s warm ochres dignify without romanticising. Hostile critics accused him of politics; yet the picture’s force lies less in protest than in a sober acknowledgement of subsistence.

The Angelus, begun in 1857 for the American Thomas Gold Appleton, shifted title and meaning when the patron defaulted. Renamed after the devotional bell, it was first shown in 1865. After Millet’s death it provoked a market frenzy - 800,000 gold francs - and later inspired legislative debate over the droit de suite. Dalí’s psychoanalytic speculation about a buried child and repressed sexuality, later seemingly substantiated by X-rays, testifies less to Millet’s intent than to the painting’s capacity to absorb projection. Its stillness, the pause between labour and prayer, remains resistant to tidy narratives.

The 1860s brought relative security. A contract for twenty-five works over three years guaranteed a monthly stipend; Emile Gavet commissioned a vast corpus of pastels - ninety in total. The Exposition Universelle of 1867 presented his key canvases to an international public. In 1868 Frédéric Hartmann ordered The Four Seasons for a considerable sum, and the French state named Millet Chevalier de la Légion d’Honneur. Yet institutional recognition never erased his sense of precariousness.

Elected to the Salon jury in 1870, he soon fled the Franco-Prussian War with his family to Cherbourg and Gréville, returning to Barbizon only in late 1871. His health declined; commissions languished. On 3 January 1875, he and Catherine regularised their long partnership with a religious ceremony. Seventeen days later, on 20 January, he died. The estate he left was modest, a disparity that fuelled arguments for artists’ resale rights.

Millet’s legacy is both formal and moral. Van Gogh revered him, copying and internalising his compositions in the Dutch years; Monet’s coastal Normandy scenes recall Millet’s late landscapes; Seurat distilled from him a structural clarity cloaked in silence. In literature, Mark Twain’s Is He Dead? recast Millet as a trickster of the art market; Edwin Markham and David Middleton found in his figures the seeds of modern social poetry. The multiplicity of responses - devotional, political, psychoanalytic - indicates an oeuvre that balances specificity with openness. Rooted in Normandy earth, forged in Parisian rejection, and ripened in Barbizon, Millet constructed a visual language of labour that refuses spectacle yet courts monumentality. His peasants do not plead; they persist.

In 1833 his father sent him to Cherbourg, first to Bon Du Mouchel, then to Théophile Langlois de Chèvreville, a follower of Baron Gros. These provincial ateliers offered craft rather than doctrine, enough to propel a stipend that in 1837 delivered him to Paris and the École des Beaux-Arts, where he studied briefly under Paul Delaroche. The metropolis did not embrace him. His scholarship lapsed in 1839, and the Salon rejected his Saint Anne Instructing the Virgin. Paris, volatile and crowded, demanded novelty and finish; Millet, still searching, retreated to Cherbourg.

Accepted at the Salon in 1840 with a portrait, he flirted with the genre that promised quickest payment - likenesses for the bourgeoisie - yet found the enterprise arid. Marriage to Pauline-Virginie Ono in 1841 brought him back to Paris, but rejection at the 1843 Salon and Pauline’s death from consumption in 1844 fractured his footing. By 1845 he was in Le Havre with Catherine Lemaire, who would bear him nine children and become his wife in a civil ceremony in 1853. Domestic obligation sharpened his pragmatism: portraits, small canvases, whatever sold.

The mid-1840s also brought friendships that mattered: Troyon, Diaz, Jacque, Rousseau - painters who, like him, turned their backs on Parisian façades for the Forest of Fontainebleau; Daumier, whose draughtsmanship and moral gravity offered a model; and Alfred Sensier, later his biographer and intermittent financial lifeline. In 1847 Millet tasted official success with Oedipus Taken down from the Tree; the next year, the state bought The Winnower. Ambition swelled. He unveiled The Captivity of the Jews in Babylon at the Salon of 1848 - large, grand, rejected by critics. He eventually painted over it. X-rays of The Young Shepherdess (1870) reveal Captivity beneath - a palimpsest born of wartime scarcity and changing convictions.

In June 1849 he settled in Barbizon, a village at the forest’s edge. The move was not mere retreat but strategic reorientation. There he could make peasant life the sustained subject, not anecdote. Shepherdess Sitting at the Edge of the Forest signalled a turn from pastoral convention toward unvarnished observation. Sensier’s 1850 arrangement - money and materials in exchange for works, without exclusivity - gave him breathing room. That year he exhibited The Sower. The figure, striding against twilight, became an emblem: not heroic rhetoric but monumental necessity.

From 1850 to 1853 he laboured over Harvesters Resting (Ruth and Boaz), his only dated painting and the one he considered his most significant. It attempted to reconcile biblical gravitas with contemporary toil, Michelangelo’s sculptural weight with Poussin’s measured order. The Salon awarded it a second-class medal. Meanwhile he etched - Man with a Wheelbarrow, Woman Carding Wool - concise essays in line and burden. His focus narrowed to the daily dramas of labour: sowing, gleaning, milking, shearing.

The Gleaners of 1857, prepared through years of sketches and an earlier vertical version, brought him notoriety. The public saw poverty and social unrest; Millet proposed endurance and rhythm. Three women bend and rise, their backs tracing arcs that echo the cyclical labour of the poor. The distant stacks of grain and a setting sun imply abundance withheld. His palette’s warm ochres dignify without romanticising. Hostile critics accused him of politics; yet the picture’s force lies less in protest than in a sober acknowledgement of subsistence.

The Angelus, begun in 1857 for the American Thomas Gold Appleton, shifted title and meaning when the patron defaulted. Renamed after the devotional bell, it was first shown in 1865. After Millet’s death it provoked a market frenzy - 800,000 gold francs - and later inspired legislative debate over the droit de suite. Dalí’s psychoanalytic speculation about a buried child and repressed sexuality, later seemingly substantiated by X-rays, testifies less to Millet’s intent than to the painting’s capacity to absorb projection. Its stillness, the pause between labour and prayer, remains resistant to tidy narratives.

The 1860s brought relative security. A contract for twenty-five works over three years guaranteed a monthly stipend; Emile Gavet commissioned a vast corpus of pastels - ninety in total. The Exposition Universelle of 1867 presented his key canvases to an international public. In 1868 Frédéric Hartmann ordered The Four Seasons for a considerable sum, and the French state named Millet Chevalier de la Légion d’Honneur. Yet institutional recognition never erased his sense of precariousness.

Elected to the Salon jury in 1870, he soon fled the Franco-Prussian War with his family to Cherbourg and Gréville, returning to Barbizon only in late 1871. His health declined; commissions languished. On 3 January 1875, he and Catherine regularised their long partnership with a religious ceremony. Seventeen days later, on 20 January, he died. The estate he left was modest, a disparity that fuelled arguments for artists’ resale rights.

Millet’s legacy is both formal and moral. Van Gogh revered him, copying and internalising his compositions in the Dutch years; Monet’s coastal Normandy scenes recall Millet’s late landscapes; Seurat distilled from him a structural clarity cloaked in silence. In literature, Mark Twain’s Is He Dead? recast Millet as a trickster of the art market; Edwin Markham and David Middleton found in his figures the seeds of modern social poetry. The multiplicity of responses - devotional, political, psychoanalytic - indicates an oeuvre that balances specificity with openness. Rooted in Normandy earth, forged in Parisian rejection, and ripened in Barbizon, Millet constructed a visual language of labour that refuses spectacle yet courts monumentality. His peasants do not plead; they persist.

13 Millet Paintings

The Angelus c.1857/59

Oil Painting

$1037

$1037

Canvas Print

$77.85

$77.85

SKU: MJF-3332

Jean-Francois Millet

Original Size: 56 x 66 cm

Musee d'Orsay, Paris, France

Jean-Francois Millet

Original Size: 56 x 66 cm

Musee d'Orsay, Paris, France

Woman Sewing by Lamplight c.1870/72

Oil Painting

$975

$975

Canvas Print

$75.63

$75.63

SKU: MJF-3333

Jean-Francois Millet

Original Size: 100.6 x 81.9 cm

Frick Collection, New York, USA

Jean-Francois Millet

Original Size: 100.6 x 81.9 cm

Frick Collection, New York, USA

Shepherdess Returning with her Flock n.d.

Oil Painting

$1052

$1052

Canvas Print

$74.12

$74.12

SKU: MJF-8378

Jean-Francois Millet

Original Size: 44.4 x 53.9 cm

Private Collection

Jean-Francois Millet

Original Size: 44.4 x 53.9 cm

Private Collection

The Young Seamstresses 1850

Oil Painting

$757

$757

Canvas Print

$61.81

$61.81

SKU: MJF-8379

Jean-Francois Millet

Original Size: 32.7 x 24.4 cm

Private Collection

Jean-Francois Millet

Original Size: 32.7 x 24.4 cm

Private Collection

The Gleaners 1857

Oil Painting

$1276

$1276

Canvas Print

$70.01

$70.01

SKU: MJF-10549

Jean-Francois Millet

Original Size: 83.5 x 110 cm

Musee d'Orsay, Paris, France

Jean-Francois Millet

Original Size: 83.5 x 110 cm

Musee d'Orsay, Paris, France

The Charity c.1858/59

Oil Painting

$766

$766

SKU: MJF-16648

Jean-Francois Millet

Original Size: 40 x 45 cm

Private Collection

Jean-Francois Millet

Original Size: 40 x 45 cm

Private Collection

The Cousin Hamlet at Greville 1854

Oil Painting

$1119

$1119

Canvas Print

$73.93

$73.93

SKU: MJF-18948

Jean-Francois Millet

Original Size: 74 x 92.3 cm

Musee des Beaux Arts, Reims, France

Jean-Francois Millet

Original Size: 74 x 92.3 cm

Musee des Beaux Arts, Reims, France

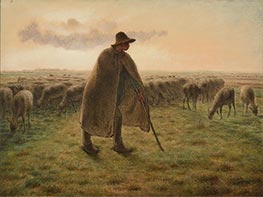

Shepherd Guarding his Flock c.1865

Paper Art Print

$66.46

$66.46

SKU: MJF-18949

Jean-Francois Millet

Original Size: 74.7 x 98.4 cm

Musee des Beaux Arts, Reims, France

Jean-Francois Millet

Original Size: 74.7 x 98.4 cm

Musee des Beaux Arts, Reims, France

Young Shepherdess Sitting on a Fence c.1866/68

Paper Art Print

$58.54

$58.54

SKU: MJF-18950

Jean-Francois Millet

Original Size: 45 x 37.3 cm

Musee des Beaux Arts, Reims, France

Jean-Francois Millet

Original Size: 45 x 37.3 cm

Musee des Beaux Arts, Reims, France

Rest in the Middle of the Day c.1865

Paper Art Print

$58.54

$58.54

SKU: MJF-18951

Jean-Francois Millet

Original Size: 36.5 x 46 cm

Musee des Beaux Arts, Reims, France

Jean-Francois Millet

Original Size: 36.5 x 46 cm

Musee des Beaux Arts, Reims, France

Portrait of an Anonymous Man c.1845

Oil Painting

$670

$670

Canvas Print

$61.81

$61.81

SKU: MJF-18952

Jean-Francois Millet

Original Size: 40.8 x 32.7 cm

Musee des Beaux Arts, Reims, France

Jean-Francois Millet

Original Size: 40.8 x 32.7 cm

Musee des Beaux Arts, Reims, France

The Goosegirl c.1866/67

Oil Painting

$669

$669

Canvas Print

$76.47

$76.47

SKU: MJF-18983

Jean-Francois Millet

Original Size: 45.7 x 56 cm

Fuji Art Museum, Tokyo, Japan

Jean-Francois Millet

Original Size: 45.7 x 56 cm

Fuji Art Museum, Tokyo, Japan

Going to Work c.1851/53

Oil Painting

$936

$936

Canvas Print

$76.99

$76.99

SKU: MJF-19716

Jean-Francois Millet

Original Size: 56 x 45.7 cm

Cincinnati Art Museum, Ohio, USA

Jean-Francois Millet

Original Size: 56 x 45.7 cm

Cincinnati Art Museum, Ohio, USA