Vincent van Gogh Painting Reproductions 3 of 18

1853-1890

Dutch Post-Impressionist Painter

416 Vincent van Gogh Paintings

Tree Trunks with Ivy 1889

Oil Painting

$666

$666

Canvas Print

$76.14

$76.14

SKU: VVG-1149

Vincent van Gogh

Original Size: 45 x 60 cm

Kröller-Müller Museum, Otterlo, Netherlands

Vincent van Gogh

Original Size: 45 x 60 cm

Kröller-Müller Museum, Otterlo, Netherlands

Undergrowth 1889

Oil Painting

$819

$819

Canvas Print

$78.50

$78.50

SKU: VVG-1150

Vincent van Gogh

Original Size: 73 x 92.5 cm

Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam, Netherlands

Vincent van Gogh

Original Size: 73 x 92.5 cm

Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam, Netherlands

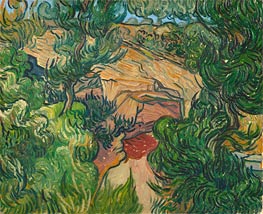

Entrance to a Quarry 1889

Oil Painting

$778

$778

Canvas Print

$81.41

$81.41

SKU: VVG-1151

Vincent van Gogh

Original Size: 60 x 73.5 cm

Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam, Netherlands

Vincent van Gogh

Original Size: 60 x 73.5 cm

Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam, Netherlands

Mountains at Saint-Remy with Dark Cottage 1889

Oil Painting

$831

$831

Canvas Print

$77.77

$77.77

SKU: VVG-1152

Vincent van Gogh

Original Size: 71.8 x 90.8 cm

Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York, USA

Vincent van Gogh

Original Size: 71.8 x 90.8 cm

Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York, USA

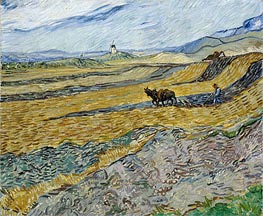

Enclosed Field with Ploughman 1889

Oil Painting

$719

$719

Canvas Print

$76.87

$76.87

SKU: VVG-1153

Vincent van Gogh

Original Size: 50.3 x 65 cm

Private Collection

Vincent van Gogh

Original Size: 50.3 x 65 cm

Private Collection

Wheatfield with a Reaper 1889

Oil Painting

$841

$841

Canvas Print

$79.05

$79.05

SKU: VVG-1154

Vincent van Gogh

Original Size: 73 x 92 cm

Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam, Netherlands

Vincent van Gogh

Original Size: 73 x 92 cm

Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam, Netherlands

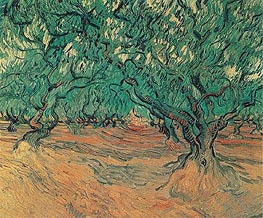

Olive Trees 1889

Oil Painting

$663

$663

Canvas Print

$65.95

$65.95

SKU: VVG-1155

Vincent van Gogh

Original Size: 53.5 x 64.5 cm

Private Collection

Vincent van Gogh

Original Size: 53.5 x 64.5 cm

Private Collection

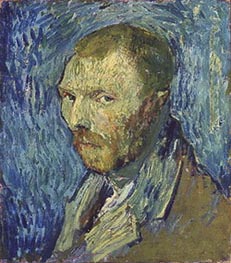

Self Portrait 1889

Oil Painting

$598

$598

Canvas Print

$75.83

$75.83

SKU: VVG-1156

Vincent van Gogh

Original Size: 51 x 45 cm

Nasjonalgalleriet, Oslo, Norway

Vincent van Gogh

Original Size: 51 x 45 cm

Nasjonalgalleriet, Oslo, Norway

Self Portrait 1889

Oil Painting

$746

$746

Canvas Print

$77.04

$77.04

SKU: VVG-1157

Vincent van Gogh

Original Size: 57 x 43.5 cm

National Gallery of Art, Washington, USA

Vincent van Gogh

Original Size: 57 x 43.5 cm

National Gallery of Art, Washington, USA

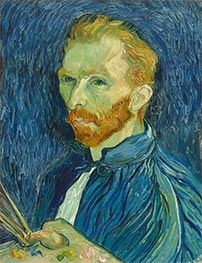

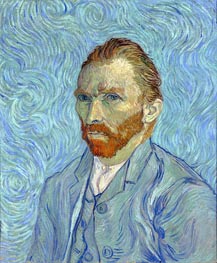

Self Portrait 1889

Oil Painting

$846

$846

Canvas Print

$82.13

$82.13

SKU: VVG-1158

Vincent van Gogh

Original Size: 65 x 54 cm

Musee d'Orsay, Paris, France

Vincent van Gogh

Original Size: 65 x 54 cm

Musee d'Orsay, Paris, France

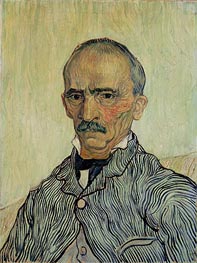

Portrait of Superintendant Trabuc in St. Paul's ... 1889

Oil Painting

$754

$754

Canvas Print

$92.71

$92.71

SKU: VVG-1159

Vincent van Gogh

Original Size: 61 x 46 cm

Dubi-Muller Foundation, Solothurn, Switzerland

Vincent van Gogh

Original Size: 61 x 46 cm

Dubi-Muller Foundation, Solothurn, Switzerland

Portrait of a Young Peasant 1889

Oil Painting

$738

$738

Canvas Print

$100.78

$100.78

SKU: VVG-1160

Vincent van Gogh

Original Size: 61 x 50 cm

Galleria Nazionale d'Arte Moderna, Rome, Italy

Vincent van Gogh

Original Size: 61 x 50 cm

Galleria Nazionale d'Arte Moderna, Rome, Italy

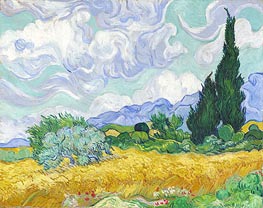

Wheatfield with Cypresses 1889

Oil Painting

$819

$819

Canvas Print

$79.05

$79.05

SKU: VVG-1161

Vincent van Gogh

Original Size: 72 x 91 cm

National Gallery, London, UK

Vincent van Gogh

Original Size: 72 x 91 cm

National Gallery, London, UK

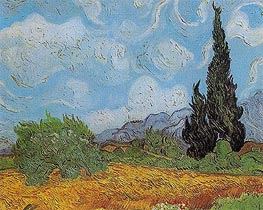

Wheat Field with Cypresses 1889

Oil Painting

$663

$663

Canvas Print

$79.60

$79.60

SKU: VVG-1162

Vincent van Gogh

Original Size: 51.5 x 65 cm

Private Collection

Vincent van Gogh

Original Size: 51.5 x 65 cm

Private Collection

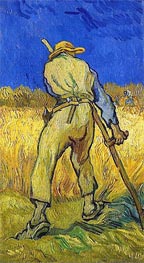

The Reaper (after Millett) 1889

Oil Painting

$557

$557

Canvas Print

$65.95

$65.95

SKU: VVG-1163

Vincent van Gogh

Original Size: 43.5 x 25 cm

Memorial Art Gallery at the University of Rochester, New York, USA

Vincent van Gogh

Original Size: 43.5 x 25 cm

Memorial Art Gallery at the University of Rochester, New York, USA

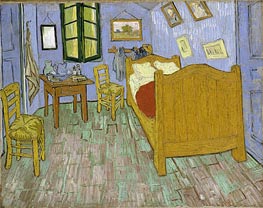

Vincent's Bedroom in Arles 1889

Oil Painting

$801

$801

Canvas Print

$79.05

$79.05

SKU: VVG-1164

Vincent van Gogh

Original Size: 73.6 x 92.3 cm

Art Institute of Chicago, Illinois, USA

Vincent van Gogh

Original Size: 73.6 x 92.3 cm

Art Institute of Chicago, Illinois, USA

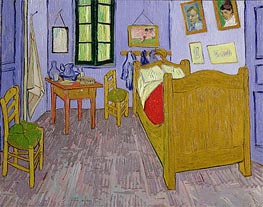

Van Gogh's Bedroom at Arles 1889

Oil Painting

$739

$739

Canvas Print

$129.25

$129.25

SKU: VVG-1165

Vincent van Gogh

Original Size: 57.5 x 74 cm

Musee d'Orsay, Paris, France

Vincent van Gogh

Original Size: 57.5 x 74 cm

Musee d'Orsay, Paris, France

Wheat Field Behind Saint-Paul Hospital with Reaper September

Oil Painting

$768

$768

Canvas Print

$65.95

$65.95

SKU: VVG-1166

Vincent van Gogh

Original Size: 59.5 x 72.5 cm

Museum Folkwang, Essen, Germany

Vincent van Gogh

Original Size: 59.5 x 72.5 cm

Museum Folkwang, Essen, Germany

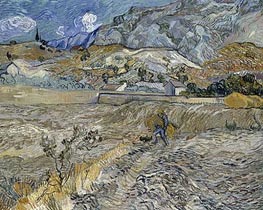

Enclosed Wheat Field with Peasant 1889

Oil Painting

$819

$819

Canvas Print

$79.05

$79.05

SKU: VVG-1167

Vincent van Gogh

Original Size: 73.7 x 92.1 cm

Indianapolis Museum of Art, Indiana, USA

Vincent van Gogh

Original Size: 73.7 x 92.1 cm

Indianapolis Museum of Art, Indiana, USA

Enclosed Field with Ploughman 1889

Oil Painting

$622

$622

Canvas Print

$81.78

$81.78

SKU: VVG-1168

Vincent van Gogh

Original Size: 54 x 65.4 cm

Boston Museum of Fine Arts, Massachusetts, USA

Vincent van Gogh

Original Size: 54 x 65.4 cm

Boston Museum of Fine Arts, Massachusetts, USA

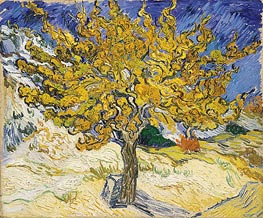

The Mulberry Tree 1889

Oil Painting

$607

$607

Canvas Print

$82.68

$82.68

SKU: VVG-1169

Vincent van Gogh

Original Size: 54 x 65 cm

Norton Simon Museum, Pasadena, USA

Vincent van Gogh

Original Size: 54 x 65 cm

Norton Simon Museum, Pasadena, USA

The Poplars at Saint-Remy 1889

Oil Painting

$662

$662

Canvas Print

$74.51

$74.51

SKU: VVG-1170

Vincent van Gogh

Original Size: 61.6 x 45.7 cm

Cleveland Museum of Art, Ohio, USA

Vincent van Gogh

Original Size: 61.6 x 45.7 cm

Cleveland Museum of Art, Ohio, USA

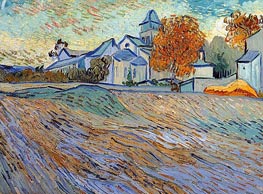

View of the Church of Saint-Paul-de-Mausole 1889

Oil Painting

$472

$472

Canvas Print

$74.14

$74.14

SKU: VVG-1171

Vincent van Gogh

Original Size: 44.5 x 60 cm

Private Collection

Vincent van Gogh

Original Size: 44.5 x 60 cm

Private Collection

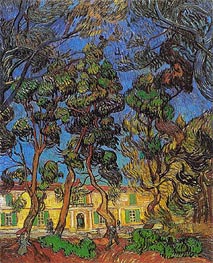

Trees in the Garden of Saint-Paul Hospital 1889

Oil Painting

$831

$831

Canvas Print

$65.95

$65.95

SKU: VVG-1172

Vincent van Gogh

Original Size: 90.2 x 73.3 cm

Armand Hammer Museum of Art at UCLA, Los Angeles, USA

Vincent van Gogh

Original Size: 90.2 x 73.3 cm

Armand Hammer Museum of Art at UCLA, Los Angeles, USA